Love and memory

With a GoPro camera strapped to her chest, Brenda L Croft is documenting her family history straight from the heart.

With a GoPro camera strapped to her chest, Brenda L Croft is documenting her family history straight from the heart.

Brenda L Croft’s father Joe was a Gurindji man and one of the Stolen Generations. Now, many years after his death, Croft is piecing together the fragments of his life in a complex multimedia work Solid/Shifting Ground.

For the past three years Croft has been trekking sections of the now heritage listed Wave Hill Walk-Off Route in Gurindji mapping what she calls her “memory-scape” with audio-visual media and photography captured with a camera strapped onto her chest, near her “heart and heartbeat”.

“Walking the Wave-Hill Track is a performative act that has helped connect me to my father’s birthplace and the strength of our people,” says Croft. “When you walk you think differently … it changes the way you breathe.”

The partially overgrown, 22km track is significant to Croft’s people who walked the same path from Wave Hill Station in 1967 to strike against the poor conditions and brutality they had experienced as pastoral workers for more than 40 years. It was a strike that eventually led to the passing of the 1976 Northern Territory Aboriginal Land Rights Act, a moment immortalised in the now iconic photo of Gough Whitlam pouring sand through the hands of Vincent Lingiari.

Croft, a Research Fellow with UNSW Art & Design’s National Institute for Experimental Arts, has been awarded a prestigious Australia Council National Indigenous Arts Award Fellowship to develop Solid/Shifting Ground, a combination of performance, creative narrative, moving and still imagery, and sound.

Like many descendants of the Stolen Generations, Croft grew up far from her customary homelands and is of mixed heritage. “Gurindji/Malngin/Mudpurra on my father’s side and Anglo-Australian/Irish/German on my mum’s,” she says.

In my mother’s garden (1998) – This is me with Mum and Dad in our Perth front yard in 1965. We were off to church on Christmas Day. Mum had made our dresses and hats – by the look on my face I didn’t want to be wearing mine. photo: Brenda L Croft

Her parents, Joe and Dorothy, were keen photographers and Croft says her interest in art and photography was sparked by the “bed-sheet-pinned-to-the-lounge-room-wall slide nights” her mother regularly organised.

Where Croft’s childhood was relatively stable, her father’s was the opposite.

Joe was removed from his mother aged around four years and grew up in government institutions including Kahlin Compound in Darwin and The Bungalow Half-caste Children’s Home in Alice Springs.

One of the first Aboriginal people to attend university, Joe was a surveyor and then public servant with the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and the Aboriginal Development Commission in Canberra. He was a close ally of Indigenous leader Charles Perkins, a childhood friend from Bungalow.

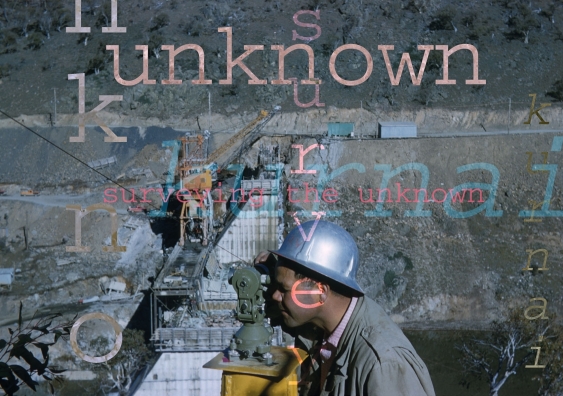

Surveying the unknown/Kurnai (1999) – Dad was a surveyor working on the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme. It was in the late 1950s and Australia was welcoming migrants, not like the anti-refugee backlash we have now. Even though Dad was possibly the only Indigenous man working there, he said there was never any prejudice on the job. The work’s also a comment on how the Snowy Scheme altered the traditional landscape of the original First Nations and overlooked their presence in the region. Photo: Brenda L Croft

Croft recalls crying in Darwin’s National Archives of Australia when she found the original records documenting her father’s removal from his community in the Police Station Timber Creek Letterbook,1926–1928.

“It was dated July 1, 1927. My father was listed as Joe (quadroon), and his (half-caste) mother, Bessie. It was the most significant moment I’ve experienced in my research.”

There have been other unsettling moments.

The artist recounts stumbling upon archival photos of her grandmother that were part of a medical research expedition documenting diseases in Aboriginal communities.

“This was the era when Indigenous people were dehumanised and basically framed as remnants of a dying race – my grandmother was photographed because she had a condition called ‘boomerang legs’, which is like rickets,” she says.

Croft will respond to these medical images using 19th century wet-plate/collodian processing for aspects of Solid/Shifting Ground.

“Indigenous history through an Indigenous research paradigm is often denied or denigrated so it’s very important to allow different ways of telling stories, in this case visually,” she says.

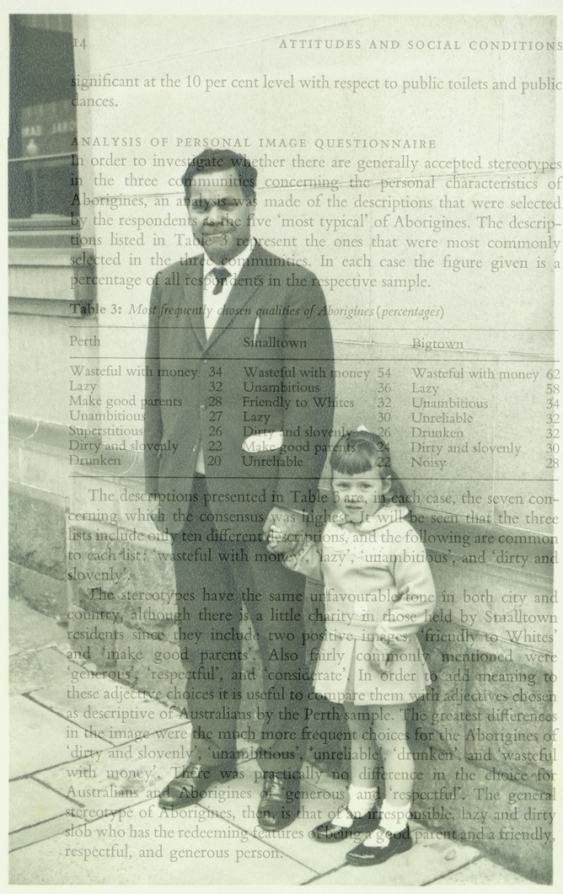

Analysis of personal image (2005) – The original photo was taken by a street photographer in Perth in 1967. Dad and I were on our way to the hospital to meet my new brother. I added the text from a questionnaire that came out the same year surveying public attitudes to Aboriginal people in Perth. It posed: Are Aboriginals ‘lazy’, ‘drunken’, ‘dirty and slovenly’? Do they ‘make good parents’? On occasion my father had been stopped in the street and asked for ID to prove I was his child because I was paler skinned than him. Photo: Brenda L Croft

Telling her family’s story also creates a lasting record for her nieces and nephew so “they know they are following in the footsteps of those who fought for equal rights for all of us”.

“I’ve discovered things during my research that have taken me on different tracks – that’s why the work is called what it is. At times I’ve felt like I’m in an earthquake and the ground, and what I thought I knew about my family, is literally shifting and changing underneath me.”

For Croft the final works, which will be staged in an exhibition in partnership with Karungkarni Art and Culture Aboriginal Corporation at the UNSW Galleries in 2017, are political as well as personal.

“This is part of a bigger, ongoing story, not just my family’s, but the history of this country and the ongoing impact of colonisation.

“Ultimately, I want to dispel the fear of difference that’s still so inherent in our society, as this is a shared history that affects all of us.”