Public demand for the use of ketamine to treat depression should not persuade medical practitioners to prescribe it before clinical trials on the safety and efficacy of its long-term use are completed, according to a leading UNSW mental health expert.

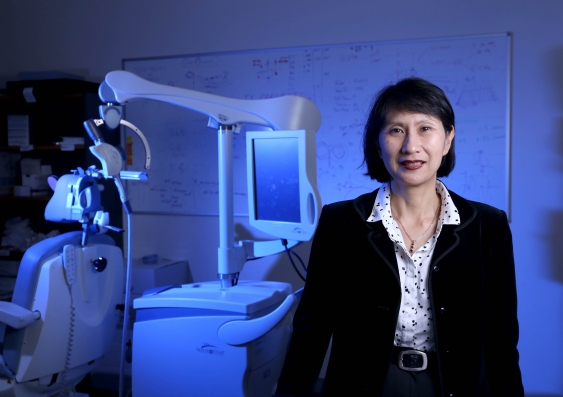

In an editorial published in the Medical Journal of Australia, Professor Colleen Loo, from UNSW’s School of Psychiatry and the Black Dog Institute, wrote that ketamine showed promising signs in single-dose trials but lasting remission from depression “remains a challenge”.

So far, the efficacy and safety of repeated dosing has not been tested in placebo-controlled trials.

“Some clinics in Australia and overseas have begun offering a course of ketamine treatments to patients with depression,” Professor Loo wrote.

“However, this practice is premature, given that the efficacy and safety of this treatment approach has yet to be tested in controlled trials.

“Further, whether such a treatment approach leads to a lasting response is as yet unknown.”

Ketamine administered in a single dose takes effect within 24 hours of administration, unlike other antidepressants, which can take several weeks.

A small preliminary study suggests it may even have comparable efficacy to, and more rapid effects than, electroconvulsive therapy, considered the “most effective proven biological treatment” for depression.

However, ketamine’s antidepressant effects typically last only several days after a single treatment.

“So far, the efficacy and safety of repeated dosing has not been tested in placebo-controlled trials,” Professor Loo wrote.

“Longer-term use is associated with different risks, and the safety of ketamine with repeated treatments is unclear.”

Uncontrolled data from recreational users of ketamine suggest those risks may include liver damage, bladder dysfunction, cognitive impairment and possible addiction.

“It is not surprising that recent actions have been taken by health authorities in Australia to curtail medical practitioners offering a course of ketamine treatments to patients with depression,” Professor Loo concluded.

“If ketamine is prematurely applied clinically to treat depression, before research has determined how and if it can be effectively and safely used to achieve lasting remission of depression, the end result may be disillusionment and even abandonment of this otherwise most promising therapy.”

A $2.1 million grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council, announced in November, will see UNSW lead Australia’s largest clinical trial to further explore the potential of ketamine as a new treatment for major depression.