Abstract World-AIDS SCT final KK (5).pdfAbstract World-AIDS SCT final KK (5).pdfTwo men who were HIV-positive appear to have cleared the virus, registering undetectable levels after bone marrow transplants in Sydney.

The patients, treated at St Vincent’s Hospital in partnership with UNSW's Kirby Institute, have undetectable levels of HIV more than three years after their transplants, the first successful cases of HIV being cleared in Australia.

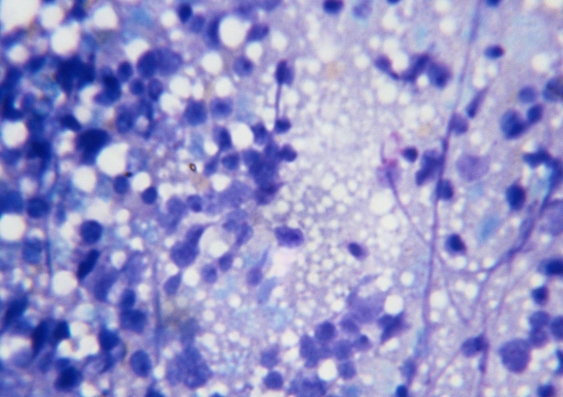

Significantly, the bone marrow the men were treated with did not contain both copies of a rare gene that affords protection against the virus.

The researchers say the results herald a new direction in HIV research and new hope for HIV positive people with leukaemia and lymphoma.

The work is being presented today (Sat 19 July) at the Towards an HIV Cure Symposium, which is part of the 20th International AIDS Conference in Melbourne.

In the Sydney cases, one patient had a successful bone marrow transplant in 2010 for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. His donor had one of two possible copies of a gene that affords protection against the virus.

However, in 2011, a second man underwent a similar procedure for acute myeloid leukaemia, but had a bone marrow donation without any genetic fingerprint that affords protective immunity.

Both cleared the virus, but remain on antiretroviral therapy as a protective measure.

“We’re so pleased that both patients are doing reasonably well years after the treatment for their cancers and remain free of both the original cancer and the HIV virus,” says the senior author of the study and UNSW Kirby Institute director, Scientia Professor David Cooper.

Until now, the only person considered to have cleared HIV is an American man, Timothy Ray Brown, who had two bone marrow transplants in Berlin (in 2007 and 2008). In that case, the second donor bone marrow included both copies of a gene that affords protection against HIV (CCR5 delta32 mutation) – which is found in less than one percent of the population. The man is no longer on antiretroviral therapy and remains clear of the virus.

In Boston, two other patients underwent similar bone marrow transplants in 2012 but the transplanted cells did not contain the CCR5 gene mutation. In both cases the virus returned after antiretroviral treatment was stopped.

“It is very difficult to find a match for bone marrow donors and even more so to find one that affords protective immunity against HIV,” says UNSW Professor Cooper, who is also an HIV specialist at St Vincent’s Hospital.

While the Sydney results are a significant development, the researchers stress bone marrow transplants are not a general functional “cure” for the up to 38.8 million people infected with HIV world-wide. Bone marrow transplantation is a difficult and costly procedure that can result in death in 10% or more cases.

“This is a terrific unexpected result for people with malignancy and HIV. It may well give us a whole new insight into HIV, using the principles of stem cell transplantation,” said Dr Sam Milliken, Director of St Vincent’s Haematology & Bone Marrow Transplantation and study co-author.

“It is important to caution that at this stage, this form of treatment is far too dangerous for treating patients with HIV alone, but there may be potential for using transplants as an effective treatment modality for HIV down the track,” says Dr Milliken.

The two existing Sydney patients will be the subject of investigations to work out where any residual virus might be hiding and how it can be controlled.

“Working out where the remains of the virus is hiding has become the big scientific question in the HIV/AIDS research community. It will be essential to understand in order to achieve a cure,” says Professor Cooper.

The first author on the study, Dr Kersten Koelsch from UNSW’s Kirby Institute, says the Sydney results do point to a new direction for HIV research: “We still don’t know why these patients have undetectable viral loads. One theory is that the induction therapy helps to destroy the cells in which the virus is hiding and that any remaining infected cells are destroyed by the patient’s new immune system.

“We need more research to establish why and how bone marrow transplantation clears the virus. We also want to explore the predictors of sustained viral clearance and how this might be able to be exploited without the need for bone marrow transplantation,” says Dr Koelsch.

For the time being, the Sydney results mean that more people who are suitable for bone marrow transplants might be able to participate in clinical trials to determine the value of this procedure.

Dr Milliken from St Vincent’s Hospital agrees: “We hope UNSW Australia and St Vincent’s Hospital will be the hub for people requiring these types of transplants.”

Currently only around six patients per year in Australia undergo such procedures.

Read the full abstract: Abstract World-AIDSSCT.pdf.

Media contacts: Susi Hamilton, UNSW Media Office, 0422 934 024 susi.hamilton@unsw.edu.au