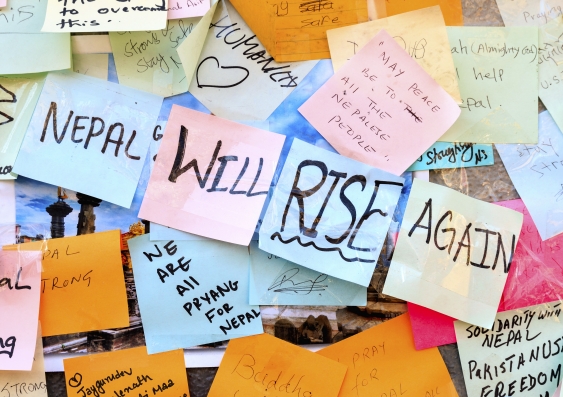

Accountability disaster in post-earthquake Nepal

Twin earthquakes devastated Nepal in 2015, but the political aftershocks have exposed much deeper faultlines, write Hemant Ojha and Krishna Shrestha.

Twin earthquakes devastated Nepal in 2015, but the political aftershocks have exposed much deeper faultlines, write Hemant Ojha and Krishna Shrestha.

OPINION: Nine months ago when two massive earthquakes struck Nepal causing 9,000 casualties, seven-year long infighting among the politicians of the new republic suddenly came to a halt. The earthquake pushed wrangling leaders to iron out major political differences and to promulgate the new Constitution in September 2015.

The crisis forced leaders to think and behave differently.

Unfortunately, however, the historic moment of the advent of the new Constitution went counter to the plight of over three million earthquake victims, as the unexpected crisis that followed paralyzed recovery efforts.

Western media vigorously covered the effects of earthquakes but remained largely unable to report the complex geopolitics of Nepal-India blockade affecting the recovery. Soon after the launch of the Constitution, a shortage of essential commodities and paralysis of transport occurred right at the time that Nepal was just about to embark on massive recovery works.

Fuel and medicines stopped coming to Nepal from India, which envelops Nepal from three sides, and through which Nepal accesses transit passage to seaports. Earthquake survivors have been badly awaiting relief supplies at chilling mountains in the winter. United Nations agencies warned that Nepal would fall into a major humanitarian disaster.

While earthquakes cannot be prevented, the geopolitical crisis could have been avoided, had conscience prevailed on all sides at such difficult times, from groups including Nepal's ruling party leaders, dissident Madheshi Morcha commanders, and South Block (Ministry of External Affairs, India) officials.

Instead of building confidence, politics turned to apathy, violence and bullying, despite all players knowing the severity of the humanitarian crisis.

For the most part, the ruling political leaders have to be accountable, but unsurprisingly, they appear to have lost sense of what it means to be a responsive government at a time of disaster. Recall that for more than three days after the first earthquake hit Gorkha on the 26th of April last year– the epicentre of the biggest earthquake measuring 7.8 in Richter scale - neither the Prime Minister nor a minister visited the area soon after the disaster.

For over a week after the deadly quake, none of the major political party leaders expressed anything in public about how they would respond to the crisis. While local groups responded quickly, doing what they could, national politics remained silent for weeks after the deadly event.

When a tsunami hit Japan in 2011, the Prime Minister, Naoto Kan, was quick to tour around and express solidarity with affected people soon after it happened. Such a prompt response by the political leadership at the time of a disaster is the defining feature of a democratic polity and accountable leadership.

Politicians could have also been more prepared, given that the earthquake risk was not unknown.

Despite repeated warnings by the scientific community for major earthquakes in the Himalayas any time, governments did little to keep people safe. The effort of the Ministry of Home Affairs, which mobilised the army and police for immediate relief and rescue, was commendable, but there was too little anticipation and institutional preparedness to deal with the crisis of such scale.

Clearly, Nepal faces a more severe disaster in political accountability than in the earthquake itself.

Just recall the political wrangling between the two major parties that delayed passage of the disaster recovery bill. The rift occurred not on some principle of the reconstruction, but on whose cadre would be nominated for the head of the new and powerful National Reconstruction Authority, which has a mandate to mobilize US$4 billion to rebuild the affected area. After several months of inter-party struggle, the head of the Authority was nominated last month. For earthquake victims, recovery leadership capacity and strategies matter a lot, but sadly these people’s appointment is part of political game of power and privilege. Indeed, party allegiance and favouritism is the only criteria in appointing people to most responsible public institutions.

In a country ruled largely by an unaccountable politics, much of the earthquake damage is not the result of a natural force - it is actually the wrong buildings, infrastructure and policies that are responsible for the damage. In a democracy with more accountable politics, one can expect that policy makers and planners make sincere efforts to ensure that buildings and infrastructure remain disaster resilient. But, as the recent Transparency International Report states, political leaders are at forefront of corruption.

A very limited sense of political accountability exists with regard to ensuring future safety of people, as such a public good is compromised for narrow and unfair private gains at the present time.

Such a deep-rooted accountability disaster does not lead to causalities in a visible way - it is the silent killer of society at large.

All political elites - from those in the power through the opposition to social movement avant gardes - reside in the capital city of Kathmandu. In all processes of contestations and democratic struggles, they have engaged in endless talks, in effect centralizing local power. Just take note of the fact that no local government election has been held since 2002.

In effect, those in power have undermined spaces of democracy at the local level so vital to disaster recovery.

International support to disaster recovery has been unprecedented, but its effectiveness is questionable. A major donors' conference in November last year has led to the commitment of over US$4.4 billion in the recovery fund. It is not yet clear how and when these commitments will be delivered, and even if the money comes, public institutions have limited spending capacity. As yet, much of the disaster recovery aid has not found its way into the huts and bellies of disaster-displaced people.

Fortunately, there is no social collapse, no dramatic rise of suicide rates and no mental health disaster – thanks to the great social capital and spirit of supporting each other at display. These local strengths of society could have been better mobilised in the process of reconstruction.

One can look at and recognise how communities and local governments have demonstrated tremendous capacity to manage risks and advance development. They have built local infrastructure, small roads, schools and hospitals.

But if there is anything political leaders have done in Nepal, that is the sabotaging of local democracy. This is an extreme form of unaccountable politics in the country.

Earthquakes and natural disasters hit local people, their houses, their assets, but the accountability disaster makes people defunct as human beings, as people are stripped of their right to seek humanitarian response in times of distress.

Hemant Ojha and Krishna Shrestha are researchers in the School of Social Sciences at UNSW.

This opinion piece originally appeared in the Kathmandu Post.