Malcolm Turnbull and the Menzies legacy

Robert Menzies' biography, which describes his success in managing both party and cabinet, is guidance Malcolm Turnbull must consider to ensure his success as Prime Minister, writes James Goldrick.

Robert Menzies' biography, which describes his success in managing both party and cabinet, is guidance Malcolm Turnbull must consider to ensure his success as Prime Minister, writes James Goldrick.

OPINION: If there is a guide that Malcolm Turnbull should turn to ensure his success as Prime Minister, it may a chapter of Robert Menzies' biography, which describes his success in managing both party and cabinet, in part through his willingness to accept when he was in the minority, writes James Goldrick.

In his victory speech on September 14, Malcolm Turnbull asserted that the government which he was about to lead would be "a thoroughly Liberal government, committed to freedom, the individual and the market".

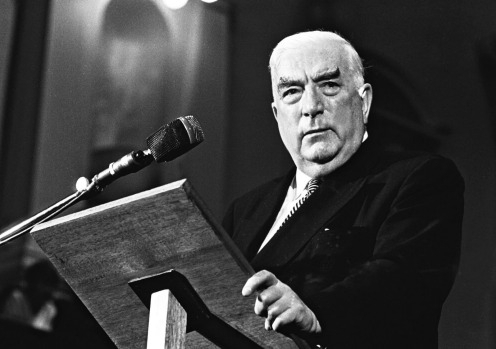

These comments invoked the shade of Robert Menzies and the first constitution of the Liberal Party – drafted by Mr Menzies – which called for a nation which looked "primarily to the encouragement of individual initiative and enterprise as the dynamic course of reconstruction and progress".

But there may be something more personal within the Menzies experience that is relevant to Mr Turnbull.

There are some interesting similarities between the two. They share extraordinary gifts of intellect and public speaking, as well as an extraordinary self-confidence that can be charismatic but can – and does - easily manifest itself as arrogance.

Both are known for a cutting tongue and a gift for invective. A young Robert Menzies would throw his weight around and pour scorn on anyone with whom he disagreed, to the point that his common insult as a schoolboy became his own nickname of 'Dag'. Mr Turnbull has never, from his own schooldays onwards, suffered fools gladly – if at all.

Both failed in their first assay at national leadership. While Mr Menzies effectively took himself temporarily out of the fight when he resigned as prime minister in 1941, it was a combination of the same reasons that were to topple Mr Turnbull as leader of the opposition nearly 70 years later.

What Mr Menzies' biographer wrote of his subject could as easily be applied to Mr Turnbull: "The main charges against him were personal: that with brilliance went arrogance ... and that, as Curtin once put it to Dixon, 'Menzies never handled his men'."

The experience of rejection forced both men into a period of self-reflection and renewal.

Mr Menzies succeeded in changing himself and the unbroken years from 1949 to 1966 as prime minister demonstrated the extent of that change. Perhaps, above all, it was because he was able to do what an old friend remarked in 1943 would be essential for him, to create a loyal group of supporters who would be loyal because he deserved "their loyalty, rather than always taking it for granted and not bothering to make the little acknowledgements which, after all, count for so much in life".

Over the last few years Mr Turnbull has clearly tried to recast himself and regain the trust of his political party in the same way that Mr Menzies did as he formed the Liberals from the ashes of the UAP during World War II.

Such a change of approach was apparent both in the emphasis which Mr Turnbull placed in his announcement of his challenge on the need for proper economic policy and his insistence that he will be fully consultative as "the first among equals".

The economic focus represents Mr Turnbull's key to co-operating with the right wing of the party that dislikes him so much, as well as the Nationals, while the emphasis on consultation is intended to reassure the coalition ministry – as well as the backbench - that he will repeat neither his own mistakes of the past, nor those of Tony Abbott.

The first step has been taken. Mr Turnbull's accession to the prime ministership may not have the clear mandate that Mr Menzies had after the 1949 election, but it does present him with the same sort of opportunity that Mr Menzies grasped – and held.

If there is a guide that Mr Turnbull as prime minister should turn to, it may be the final chapter of the second volume of Mr Menzies' biography, which describes his success in the management of both party and cabinet, perhaps most notably, in part through his willingness to accept when he was in the minority.

Mr Menzies clearly was able to manage his faults and guard his tongue – and somewhere, in the process of doing this, he became the leader he needed to be.

Rear Admiral (Rtd) James Goldrick is a naval historian and an adjunct professor at UNSW Canberra (ADFA).

This opinion piece was first published in The Canberra Times.