Three Great War histories review: Was the slaughtering really worth it?

Reading Ham and Gerwarth's sombre narratives beside FitzSimons' nationalist boosting shows he really doesn't understand the Great War, writes Peter Stanley.

Reading Ham and Gerwarth's sombre narratives beside FitzSimons' nationalist boosting shows he really doesn't understand the Great War, writes Peter Stanley.

REVIEW: Maaate! Beaudy! We bored it up those bastard Brits, eh! Villers-Bret – the Aussies' triumph. Those mighty Anzacs attacked straight into Hun machine-gun fire – rat-tat-tat! – and through shell-fire – ba-boom!

And they dished it to the Fritzes – kamerad my arse! – and saved that French village and the whole bloody Western Front and damn near won the war. 'Onya, Diggers. Not that Field-bloody-Marshal Douglas Haig noticed. Again. I coulda cried: Maaate!

I did weep. There you have the digested read of Peter FitzSimons' latest house-brick-sized book, Victory at Villers-Bretonneux, completing his trilogy on Australians in the Great War. Thank goodness.

FitzSimons' style is that of a graphic novel without the pictures; cartoon history by the kilogram. His popularity stems partly from the promotional advantages he enjoys with media outlets in all forms, but also because he is a sort of historical Trump – he understands and expresses (and probably shares) a simple patriotism that transcends the complexity of real life, and tells a good story regardless.

As his acknowledgments make clear, practically all the actual research for this and other books is done by a large team of elves – FitzSimons' part is to render it in what he concedes is "a particular, unconventional way". It is story-telling: but is it history?

No one would dispute that the counter-attacks at Villers-Bretonneux were among the AIF's most impressive feats – like most writers, FitzSimons takes his cue from Charles Bean, who said as much in his dispatches, diaries and in his official history. And few would doubt that the episode's principal architect, Brigadier-General Harold "Pompey" Elliott, was Australia's greatest fighting soldier of the war. That's been confirmed many times since 1918.

What is in contention – what this book makes contentious by FitzSimons' focus and style – is whether this action, tiny on the scale of the Western Front, deserves the nearly 700 pages of adulation, simplification and exaggeration it gets at his hand. This is all, as FitzSimons would say, pissing in the wind. His thousands of readers have their Oi, oi, oi prejudices confirmed; he enjoys his status as Australia's highest-earning non-fiction writer (though many passages are actually imagined) and historians who see the past less simplistically are left looking like sour-pusses. But as Fitzy writes: "Bingo. Done. Move on."

Paul Ham is also a former journalist who has become a best-selling popular historian. His Passchendaele: Requiem for Doomed Youth is also a house-brick-sized product, but it is quite a different proposition from FitzSimons'.

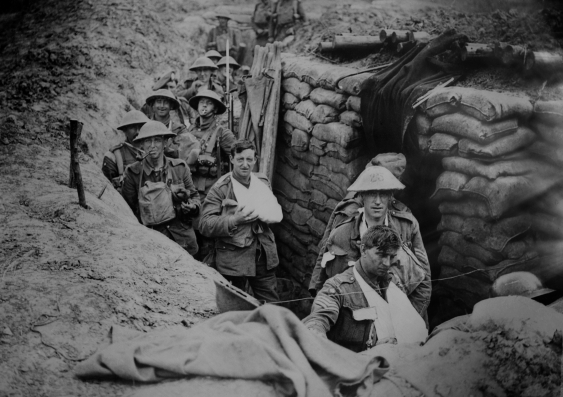

Next year will see another round of Great War anniversaries, notably that of the third battle of Ypres, when half a million British empire and German troops became casualties in slogging British offensives in the mostly rain-sodden Flanders autumn. They shifted the front line by at most about five kilometres. From the huge Tyne Cot cemetery near Passchendaele (the village whose name now stands for the entire battle), the city of Ypres is quite clear on the horizon: surely all visitors question whether the gain was worth the cost.

Ham has written a string of acclaimed popular histories; all fat volumes, testifying to both his tenacity as a researcher – he does his own – but also his desire to be taken seriously. No historian I know quotes philosophy as much as Ham, who seems anxious to establish his gravity. He really needn't worry.

Passchendaele is a solid if somewhat old-fashioned account of one of the Great War's most terrible battles (it is one of just four chosen by the British government to be commemorated during the centenary, a sign of its continuing power). He describes it all soberly and meticulously, without need of a rat-tat-tat or a ka-boom.

Ham creditably refuses to accept well-worn nails in Field Marshal Douglas Haig's coffin, such as the celebrated anecdote in which his intelligence chief, Lancelot Kiggell, was said to have gazed at the muddy crater-field of Ypres and asked "did we really send men to fight in that?". The story is, at best, apocryphal. But Ham does describe how a British colonel did try to tell headquarters staff the truth, and was "reprimanded for his effrontery".

The core of Ham's condemnation of the idea and execution of the Ypres offensive is that it was planned as a battle of "attrition" – intended to kill Germans rather than capture the Belgian coast (to impede German submarine warfare). The bulk of Passchendaele is a detailed, even-handed narrative that, fulfilling his title, laments the "doomed youth" who suffered through it. (Ham's sub-title is a nod to war poet Wilfred Owen's Anthem for Doomed Youth, written while the offensive continued, though oddly he doesn't say so.) In that every generation needs to know what this ugliest of battles entailed, this is a worthy service, if accomplished at wearying length.

But if Lancelot Kiggell was right, that "Boche-killing is the only way to win war" – in this war at least – then it is hard to see what other options Haig, or anyone else, had. If a negotiated peace was impossible – and that seems to have been so – then resolution in battle was the only way to end the war. If a breakthrough was impossible, as seemed to be the case after the Somme, then an attrition battle seems to have been unavoidable.

Ham chastises Haig for pretending that he could have broken though the lines of German pill-boxes, but he, like Haig – like all of us – can offer no credible alternative to the tragedy of Passchendaele.

Ham takes issue with revisionist historians who have recently challenged the traditional war-poet-led condemnation of Haig and his plans, who have presented Passchendaele as justifiable. He blames Haig for persisting with the slaughter knowing that breakthrough was impossible, but also Prime Minister Lloyd George for letting him, and the politicians of Europe for unthinkingly committing the world to a war in which Passchendaele was the logical, inevitable outcome.

The most important pages in Ham's book are the ones many readers will not have the stamina to reach. His epilogue makes a thoughtful contribution to the all-too-rare discussion of why it is necessary or desirable to "remember" the dead of the Great War, something, as he says, taken for granted and all-too conventional. He enlists George V to remind us that the dead of Passchendaele are a warning to be wary of regarding that war, or any war, as "necessary".

Books on the Great War tend to finish at the Armistice. Robert Gerwarth, of University College Dublin, reminds us in The Vanquished that for many the war did not end on November 11, 1918. Formerly Ottoman Iraq, for example, rose in a violent uprising against British occupation (something that might have offered a cautionary lesson had anyone in the Pentagon, Whitehall or Russell Hill realised it in 2003).

Gerwarth's book explains the conflicts that few Australians knew of then and fewer still understand now – the Russian-Polish, Romanian-Hungarian, and Greco-Turkish wars, civil wars in Ireland, Finland, Germany and Russia and the bloody aftermath of its revolution – confrontations that simmered even as the Allies imposed their "peace" treaties.

Gerwarth, originally German, draws on pan-European sources – his bibliography includes more than a dozen books by authors whose names begin with Z: Zadgorska, Zamoyski, Zorn. The Vanquishedoffers a valuable corrective to FitzSimons. Not only did 20 million die in the war, but another four million in the violence that followed, much of it pursued with brutality in ideological or ethnic contests in which defeat meant displacement if not death.

Reading Ham and Gerwarth's sombre narratives beside FitzSimons' nationalist boosting shows he really doesn't understand the Great War at all.

Peter Stanley is Professor and Director of the Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict and Society at UNSW Canberra. His most recent book is 'Armenia, Australia and the Great War'.

This opinion piece was first published in The Sydney Morning Herald.