Why good men need to reclaim masculinity from the toxic cliche of power and aggression

Good men have a responsibility to push back against the toxic aspects of masculinity, writes Darren Saunders.

Good men have a responsibility to push back against the toxic aspects of masculinity, writes Darren Saunders.

Suddenly my dad and his mate were on their feet, staring down a young bloke at the other end of the train carriage.

I didn't see what started it, but he had obviously crossed a line with the young woman next to him.

Faced with their glare and unmistakable intent he backed down and shrunk into the night at the next stop.

The moment is seared in my memory, speaking to the power of setting an example, and the importance of calling out bad behaviour.

It made a deep impression on a young boy trying to figure out — like all boys growing up — what it means to be a man.

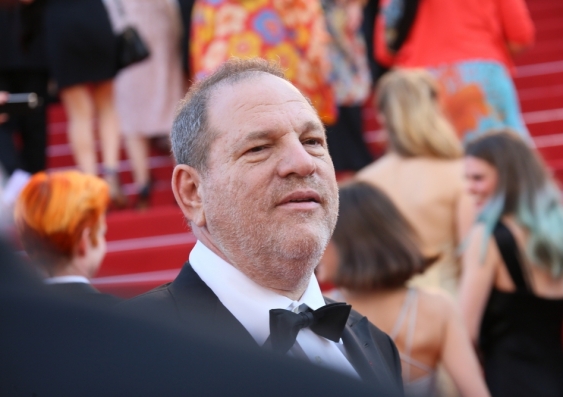

This memory assumed new relevance in the wake of the recent allegations of Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein's systematic sexual harassment of dozens of women in the film industry.

The torrent of chilling stories of assault and abuse from victims around the world has since stirred important conversations about why men like Weinstein feel they can get away with this behaviour, and why men who knew of his misconduct did not speak up.

But they've also raised fundamental questions about the kind of masculinity we should celebrate, about what it means to be a good man, and how we go about raising good boys.

Young men and boys are subjected to enormous pressure to conform to a damaged and damaging kind of masculinity, reinforced by stereotypical examples of "real men".

Apparently successful but deeply flawed blokes have high profiles in politics, sport, science, business and media.

Their success is often defined through a narrow lens of masculinity based on aggression, power, authority, promiscuity and stoicism.

But although many men still identify with this "toxic" version of masculinity, it is failing all of us.

It's not just the countless women subjected daily to men's domestic and sexual violence who suffer when this kind of masculinity is allowed to flourish. Evidence suggests it is damaging men, too.

A recent survey of over 1,000 men aged 18-30 in the US, UK and Mexico, for example, found that young men who embraced rigid cliches of manhood and how "real men" should act were more likely to suffer depression, engage in self-harm and display risky behaviour like binge drinking and dangerous driving.

These young men were also more likely to experience and perpetrate verbal, physical and online bullying.

Indeed, American sociology professor and author of Angry White Men, Michael Kimmel, says the "real man" stereotype leaves many men frustrated and angry when their unrealistic expectations — of power and dominance, for instance — aren't met.

He argues we need to champion a fairer, gentler notion of manhood, shifting our focus from being "real men" to being and raising "good men".

Photo: Shutterstock

When I put this question to a number of objectively good men from various walks of life, they listed universal qualities like integrity, empathy, strength and fairness.

In other words, being a good man is fundamentally about being a good human.

But passive acceptance of these values, even leading by example, is not enough. Good men have a responsibility to push back against the toxic aspects of masculinity.

We must stand up when it matters: Call out bad behaviour, challenge our friends and colleagues in conversation, and make it clear that even casual sexism will not be tolerated.

Writer Lindy West distils the essence of this response down to a simple question: "Do you ever stick up for me?"

However, as West rightly points out, men who speak up risk being ridiculed, and excluded from social or professional groups.

(Even though it may not feel like it, evidence suggests men are not penalised professionally for publicly advocating for diversity and equity.)

It's also important to recognise that speaking up or intervening means risking being subjected to violence. It takes real courage to put yourself in harm's way to stand up for what's right.

But isn't courage one of those universal examples that we admire in both men and women?

Of course, changing entrenched attitudes and behaviours in grown men is a daunting and difficult task. Many men benefit from their embrace of traditional masculinity, often at a heavy cost to others.

The kneejerk reaction to any challenge to this stereotype is a predictable response to a perceived loss of privilege.

But the significant physical and mental health burdens associated with traditional masculinity suggest that men have much to gain by rejecting the "real man" stereotype.

Which is why we need to find a way in modern society – with omnipresent cameras and social media – to allow space for boys and young men to make mistakes and learn from them.

Facing the consequences of bad decisions is fundamental to that learning experience.

It's one reason why dismissing bad behaviour with "boys will be boys" doesn't cut it in 2017, and it's a short arc from there to "when you're a star, they let you do it".

An important aspect to this is in helping boys understand that taking responsibility and standing up to defend what's right is an act of strength, not an expression of weakness.

While painful for many women, the allegations against Weinstein and others have smashed open a window of opportunity for good men to harness fresh momentum and take action.

Good men need to reclaim masculinity and forge a definition guided by ethics and empathy.

We need to demonstrate that being a real man means being a good man, and celebrate diverse examples of good men.

We owe it to ourselves to define and defend masculinity in a modern context, and we owe it to the generations of men and women coming after us.

We have to stop hanging the expectations of a tired cliche around the necks of boys.

Dr Darren Saunders is a Senior Lecturer in Medicine at UNSW.

This article was originally published on ABC News