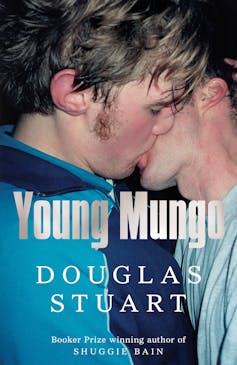

In the suspenseful opening to Douglas Stuart’s second novel, Young Mungo, it is not clear if 15-year-old Mungo is being abducted or freely going with the two men who collect him from his mother.

After the first dozen or so pages, it gradually becomes apparent that the men, “two alkies” that his mother had met at a meeting of Alcoholics’ Anonymous, are walking him through the suburbs of Glasgow with her permission, taking him out of town on a fishing expedition for “masculine pursuits”. The men’s distorted interpretation of that phrase is revealed only in the second half of the novel.

Working-class Glasgow, late 1980s

Like Stuart’s first novel, the Booker prize-winning Shuggie Bain, this one is set in Glasgow and the chief protagonists, the Hamilton family, live (like the Bain family) in one of the city’s working-class housing schemes.

Young Mungo appears to be set at about the same time – that is, in the late 1980s, when the Thatcher government was shutting down the Glasgow shipyards and dock workers were being “laid off by some suit-wearing snobs in Westminster who couldnae find Glasgow on a map, who didnae give a flyin’ fuck if the men had families to feed”.

Subtly, by degrees, Stuart introduces his readers to the violence on the Glasgow schemes that infects the lives of the teenage Mungo, his family and neighbours – almost as pervasively as the damp that seeps into their apartments and stairwells.

Mungo is a sensitive boy who is afraid of his older brother Hamish’s violent physical outbursts. Close to his older sister, he both depends on and protects her.

He didn’t like Jodie to come home to an empty house. He wanted to have the lights on before she returned from the café.

Emotionally enmeshed with his mother, unable to resist her drunken pleas to share her bed, his behaviour is often puppy-like: biting a windowsill, for instance, when overwhelmed by the intense emotional squalls that rage in his family.

His mother Maureen insists that her children call her “Mo-Maw”, because she wants strangers to think that she is their older sister. Nicknamed “Tattie-bogle”, from when the children first noticed how “vindictive and rotten” she could become after sustained drinking, she is incapable of motherhood and struggles to keep her life together between drinking bouts. Mostly out of work and unable to care for her children, Mo-Maw seeks love with her on-off boyfriend “Jocky” – or when he rejects her, in the arms of single men from other flats on the stairwell.

One afternoon when searching for his mother, Mungo visits Jocky’s pawn shop and over a cup of tea, the latter advises him:

“At ma age love is a nuisance of a thing. What ye want is some easy company on a Tuesday night … and if yer lucky a bit of nookie as long as ye can both lie on yer side while ye’re at it.”

As this excerpt suggests, Stuart weaves Glaswegian argot into his novel to good effect. Most of the jargon is intelligible, although some readers might need an internet search engine to translate words like “oxter” (armpit), “scunner” (a strong dislike) and “sleekit” (artfully flattering or sly).

Hamish justifies his bullying and tormenting of Mungo on the grounds that he wants to “make a man” of him, in much the same way that Mo-Maw did when she sent him on that fishing trip with two alcoholic men. They were St Christopher – a homeless man in his 50s who lived in hostels and sometimes the gutter, and wore tweeds and brogues; and Gallowgate – a heavy-drinking, sexually boastful carpet layer, about Hamish’s age and very much like him. “They were moody, self-made demigods who demanded constant offerings and could turn vengeful for no reason.”

Cautionary tales against enforcing masculinity

There are cautionary tales here for mothers and brothers who think they know what’s best for sons and younger brothers, whether gay or not. “Making a man” of someone is entirely subjective – and can be cruel and wounding, both mentally and physically.

The all-pervading violence in Hamish’s life includes not only beating and intimidating Mungo (“Ye’re that soft I’m surprised you have enough bones to stand upright”), but also territorial battles with the gang he commands, fighting with Catholic youths. He and his gang members steal cars, vandalise work depots and when bored, sniff glue or bait the elderly, effeminate Mr Calhoun, also known as “Poor-Wee-Chickie”, till he responds. They:

feign injury, batter him, and remind him of his low place … This one man made them feel better. When everyone looked at them like they were nothing … he still had less.

This nicely encapsulates how physically violent masculinity keeps the sexual order in place. Meanwhile, Hamish himself has a nice little sideline in selling “dank” hashish to university freshers from southern England and Edinburgh, for whom he has nothing but a smiling contempt:

Ah think they’ve had the Walkman too loud when their mammies were telling them about Glesga being full of peasants. Daft cunts thought she said it was full of pheasants.

Mungo’s life is, however, not entirely loveless, nor devoid of compassion and kindness. The people who love Mungo are his sister Jodie and his boyfriend James. The people who are kind and care for him include their neighbours, Mrs Campbell and Poor-Wee-Chickie.

Jodie, a bright student, is also Mungo’s surrogate mother. Astute and insightful, she’s often in battle with their mother over the care Mo-Maw fails to provide him – and furious to the point of violence at Mo-Maw’s abandoning them while she dates Jocky and cooks for and looks after his children. To improve her chances of getting a place at Glasgow University, Jodie has casual sex in a caravan park with her history teacher: “he would sweat on top of her for four minutes and fall fast asleep”. For money to feed Mungo and herself, she has a part-time job in an Italian cafe.

Class wounds

Because of the sectarian divide on the scheme and in the East End where the Hamilton family live, James and Mungo should not have become friends, let alone boyfriends. At their first meeting, however, it is clear that James might be the first male that Mungo can trust: “When he handed him something, Mungo didn’t need to flinch.” On parting after that first meeting, James asks Mungo: “Haud on. Will you come back the morra?”

And so a budding friendship begins. On their first night sleeping together (no sex), the boys exchange stories of their mothers’ cooking and care. James, whose own mother is dead, is acutely aware of Mo-Maw’s inadequacies as a parent; when Mungo tells him that, on the death of his father, she said she was “going to put herself first”, James replies: “that’s not what mammies are supposed to do”.

Stuart embeds class awareness in his pages with a delicate touch. For example, there’s a nice, passing observation of “mothers who rubbernecked from warm Saabs” as Mungo’s mother serves hot food to lorry drivers from a caravan on a traffic island. On another occasion, as Mungo goes out in search of Mo-Maw, he passes “good families … settled in front of their televisions” along the way, as well as “grand buildings, heavy with Corinthian columns, that the Tobacco Lords had built for themselves”.

Stuart expertly conveys Mungo’s philosophical acceptance of how his family is treated – the class wounds, if you like – and the treatment he endures from his violent older brother and neglectful mother. His bond with Jodie, his love for and belief in James, and the kindness and help he receives from Poor-Wee-Chickie sustain him through most of his torments. He’s similarly sustained by his slightly paradoxical determination to see some good in his brother Hamish and his mother, notwithstanding their “mercurial” treatment of him.

There is, in other words, a welcome absence of resentment or anger for class injuries that do not necessarily kill or cripple the principal characters.

Young Mungo is a celebration of two young gay men’s survival and love. Stuart makes clear which characters (and by implication, which types) he regards as responsible for perpetrating the sexual, gendered violence that almost destroys Mungo, James and others like them.

I suspect that he does so to show that the violence on the schemes is not something that occurs because the people living there are violent by nature or birth. Instead, he provides an insight into the structural reasons behind it, such as poverty, urban decay and other collateral damage which Zygmunt Bauman argued accompanied de-industrialisation.

Stuart implicitly rejects the idea of imposed manhood, as epitomised by the clichéd catchphrase “man up”. At its core lies an unsubtle understanding of what is a man and what young men should/ought/must become in order to resist the bullying of dominating or physically violent males like Gallowglass and Hamish. (Poor-Wee-Chickie, for instance, has considerably more moral courage than Gallowglass and Hamish, but would not know how to “man up” in the traditional sense.)

And that brand of “manning up” can reinforce a corrupted form of masculinity where certain males believe that they are omnipotent. We in Australia have seen that played out in East Timor, Afghanistan (the ongoing Ben Roberts-Smith libel case) and the Australian Defence Force Academy (where bastardisation of new cadets goes back at least three decades), among other places.

Stuart’s second novel is, like his first, a nicely told story of working-class life and love in Glasgow. He explores the possibilities that exist – almost against the odds – for young gay people in the housing schemes, or similarly impoverished settings, to find secure love.

Without preaching, Young Mungo underlines how alcohol affects not just the “alkies” themselves, but also their children and friends. And crucially, it shows how violent, dominating masculinity affects not just its perpetrators, but the men and women who are their friends, family and neighbours.

Peter Robinson, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.