Virtual reality game an innovative approach to manage pain

The character-driven game builds a bond between the user and a virtual dog companion to help develop patient resilience and coping skills.

The character-driven game builds a bond between the user and a virtual dog companion to help develop patient resilience and coping skills.

Ben Knight

UNSW Media & Content

(02) 9065 4915

b.knight@unsw.edu.au

A virtual reality (VR) game featuring a little dog and a simple quest offers a non-pharmacological alternative to acute pain management.

The immersive game, Finding Home, builds rapport between the user and dog, developing patient resilience and coping skills. As such, it presents a compelling distraction to help reduce high dose opiates.

This character-driven approach is an innovative take on VR use for pain management, says Director of the 3D Visualisation Aesthetics Lab at UNSW Sydney, Scientia Associate Professor John McGhee, a lead researcher on the project.

By introducing a canine character as a companion in its quest, the game provokes stronger attachments with its users, he says.

“It’s about building connection with character. We designed this little dog – it’s super cute – and you’re in this very abstract landscape, and you’ve got to take the dog home.

“You’re investing in the [dog’s] character, rather than just investing in yourself, which moves you away from the internalisation of pain.”

The project is a collaboration between UNSW and St Vincent’s Hospital Pain Medicine Department, Sydney, and is funded by the St Vincent’s Curran Foundation and Samsung. The prototype is currently being tested through the Acute Pain Service at St Vincent’s Hospital.

The project moves to explore alternatives to acute pain relief to complement opioid intervention and, in so doing, to minimise the risk of chronic pain, says Professor Steven Faux, Director of the Department of Pain Medicine at St Vincent’s Hospital.

“Reliance on medication alone makes people feel passive in their pain management. By contrast, studies engaging with virtual reality have shown that it can decrease anxiety and distress, thereby helping to control pain levels.

“Sometimes, you just feel stressed and uncomfortable, and the only thing you can do is take an opiate, which is not always the right thing to do. A/Prof. McGhee and I have worked on technologies to give them an alternative.”

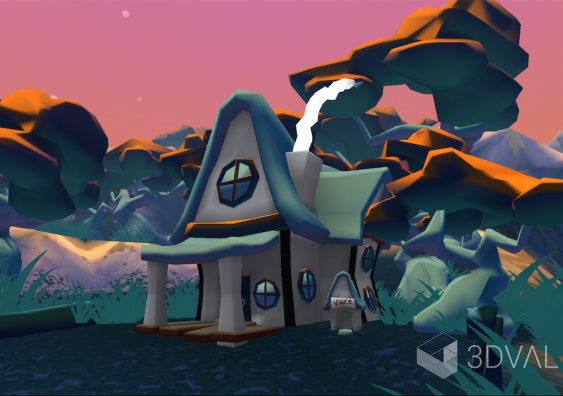

Users navigate an island, following a trail of lanterns through a series of settings, to take the dog home. Image: 3D Visualisation Aesthetics Lab.

Computer animation artists, virtual reality/gaming designers, psychologists, and pain specialists have co-designed the VR game. Users navigate an imagined landscape trying to help the dog find its way home.

“To practice the controls, you throw sticks, and the dog has to bring them back. Then you do a number of activities with the dog, building a bridge, finding a rainforest. You have to find the parrots in the trees. It’s very Australian,” A/Prof. McGhee says.

Using research and published evidence to guide the program's design was also a key focus of the team.

“There have been lots of lessons learned in past research about the types of imagery, visual and audio stimulation that can help people experiencing pain,” says Dr Christine Shiner, a senior researcher on the project from St Vincent’s, Sydney. “This research helped inform the design of the program, to make it more than just a ‘game’.”

The game uses cool hues – notably blues and purples – to placate patients’ pain response.

“We’ve developed the environment to keep the patient feeling cool, so we avoided reds and really intense colours – it doesn’t look like a real place – that’s informed by the psychology of aesthetics,” A/Prof. McGhee says.

“[It’s about] trying to cool them down, moving away from that red-hot white pain feeling towards a cool self-soothing environment.”

The aesthetic is cartoon in style to maximise the equipment's capabilities and to minimise the threat of the unfamiliar, A/Prof. McGhee says. “It’s a portable headset, so it has some limitations… so we had to be smart with the design.”

Additionally, he says it had to accommodate patients being bed-bound, engaging purely through head movements. “We had to make the interface conducive to that very restrictive movement while still feeling immersive and interactive.”

The spaces, the palette and the interactions are all informed by research to create a positive, healing environment. “All these little microtransactions and interactions, they’re all there to make you feel safe. And in doing so, it takes your attention away from simply pressing the opioid button,” he says.

By introducing a canine companion, the game provokes stronger attachments with users, says lead researcher A/Prof. John McGhee. Image: 3D Visualisation Aesthetics Lab.

Ultimately, the team aims to build artificial intelligence into the dog and introduce additional levels to the game if the initial trials are successful, A/Prof. McGhee says.

“You could build resilience into the dog, so the more you play, the better the dog copes and gets on with things… like a Tamagotchi [the handheld Japanese digital pet], you keep coming back to it.

“We wanted the game to have this kind of stickiness to it, so it wasn’t just a one-hit-wonder,” he says.

Prof. Steven Faux says: “Our initial results with the prototype have been very positive. If the trial shows marginal improvements, it’s a win-win. As a non-pharmacological intervention, the game has multiple advantages: the less reliant on medication the patient is, the better the long-term outcomes.”

If the VR gaming prototype trials deliver on their promise, the platform has commercial potential, A/Prof. McGhee says.

“If we get this right – if we can show evidence that it works – we could license it to other hospitals, distribute it more broadly.”

The game exemplifies how creative skills such as visualisation and animation can be re-tasked to directly impact health outcomes and quality of care in clinical settings, A/Prof. McGhee says.

“A lot of it boils down to story, whether it’s immersive, interactive or a linear animation. Storytelling provides a powerful tool for better informing patients, and the general public more broadly, about treatment and the nature of disease and other health messages.”

A/Prof. McGhee’s previous research collaborations have included immersive platforms that simulate scientific phenomena, such as personalised scans of strokes to help patients understand their treatment (again with St Vincent’s), drug interactions with cancerous cells, and educational 3D animations demonstrating the power of soap against COVID-19 particles.

“Our production on the activity of soap on the COVID-19 virus, for example, the quality of the output was world-class. It was recognised by prestigious animation festival SIGGRAPH Asia. For a small, highly effective animation lab to get a foothold there says something,” he says.

A/Prof. McGhee received the inaugural Distinguished Research Award for his work with the ARC Centre for Excellence in Convergent Bio-Nano Science and Technology and was nominated for the 2020 Eureka Prize. He also recently participated on a panel at the internationally renowned Unity for Humanity Summit 2021 that celebrates innovation for social change.

The 3D Visualisation Aesthetics Lab harnesses creative practice, technical innovation and immersive platforms to create world-class 3D animation and data visualisation. Their research contributes to virtual world design, science education and engagement, biomedical communication, patient interaction and immersive storytelling.