What is the gender mix like in the robotics and artificial intelligence industry?

Mari Velonaki: Women are still a minority. In my first robotics lab in 2003 I was the only woman academic for years and I never had female students. Now it's very different. I do have women students. And as a matter of fact, some of the best researchers I discovered at UNSW, especially in the area of AI, are women.

So one of the important questions facing us as educators in social robotics, is how do we develop programs and initiatives for emerging researchers, for young women? First of all, we want our young women to know there’s a space for them. We also want to communicate that we need women and researchers not only from STEM areas to work in this area. Until recently, women may not have realised that you can contribute as a psychologist, as an ethicist, as a designer, or as a media person in social robotics.

The message we want to give out is that if you’re a woman and you’re interested in this field, know that there’s a space for you, not just because you’re a woman – although women’s perspectives are always valuable – but because your expertise is so relevant to us, regardless of gender.

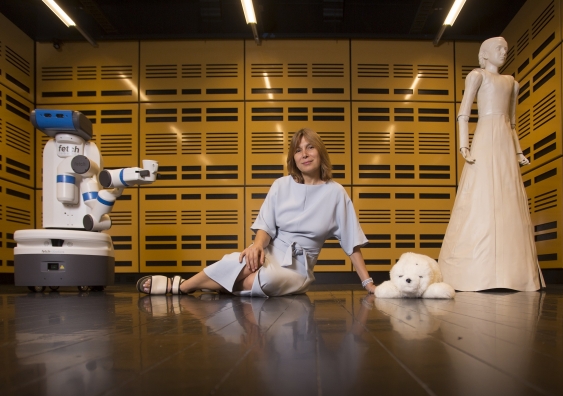

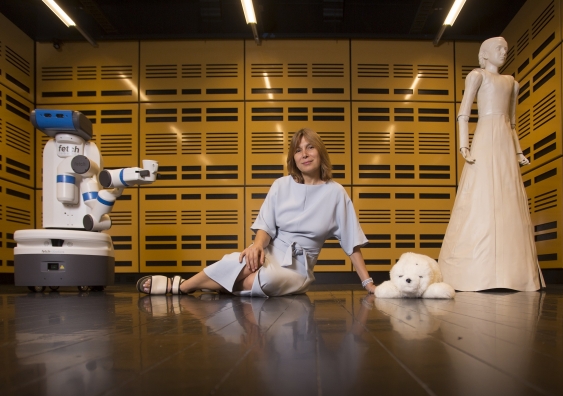

Professor Mari Velonaki and friends in the Creative Robotics Lab. Photo: Quentin Jones

If it is still the case that there is bias in the industry, how does gender affect robot design?

MV: Yes, there is a bias. There's a bias still in male representation for robots doing heavy manual work while a robot working in a reception-type role is more likely to be a female because there is the association with females being friendlier.

I think that the social and philosophical discussion about robot representation and gender needs to take place at a much more engaging, deeper level other than around traditional male and female representations. “Why do robots need to have a gender at all?” is a question that many researchers, including researchers in our lab like Dr Belinda Dunstan, have.

I am not convinced that realistic interpretations of human inspired robots is the best way to engage people as sometimes “less is more”. More abstract robotic forms can allow a person to make their own interpretation of what that robot represents to them. As humans we have an innate tendency to anthropomorphise everything, including inanimate objects – for example people naming their cars.

But this is different from actually assigning gendered roles to robots – this heavy lifting robot is male, that robot that cares for our health is female. That points to bigger problems that we have that are societal, that gender these days among young people especially is not so black and white.

So what we design for robots needs to reflect society, and gender right now is being redefined. I still think we have very old stereotypes of robots. The robots that we design right now – even including my own – are not the robots we deserve as a society. We have to be more creative in our thinking. I’m not meaning to be didactic and saying “don’t do this”. I’m saying, “don’t do only this, think of what else we can create that may well be beyond gender”. It may be that what we want in robots may not already exist, which is the approach that the Apple designers had before they created the iPhone.

PARO the therapeutic robotic seal can have a calming effect on patients, similar to animal-assisted therapy. Photo: Shutterstock

Leaving aside gender, do robots need to be humanoid at all?

MV: No, I think it’s good to try alternative designs, and then we’ll know. What I think in answering this question is irrelevant because we don’t have enough data to prove it. But by experimenting with new robotic forms, some which may not be human at all, and exposing them to the public, is the only way to know.

Social robotics would be useful when they can create engaging experiences for people, not only as a receptionist or in a busy airport or helping people when they're lost, but imagine robots for rehabilitation that assist people to live in their home longer instead of going to the nursing home. Robots that help people to maintain their dignity. It may turn out that we prefer them to be humanoid, or even gendered, or purely abstract but we need to be informed by more evidence and systematic investigation into robot form and representation in the area of Human Robot Interaction.

Is there evidence of a gender bias in the robotics industry when you design robots for function? For example, for a long time crash test dummy data was taken from dummies the average size of a man while women were an afterthought.

MV: Yes, I alluded to the examples earlier about male gender assigned to robots doing heavy lifting. I’ve also seen future robot designs in a peace keeping ‘green zone’ which were male and looked quite intimidating, probably to make people feel like they have protection. But we already know that women are also part of defence forces the world over. So again, there's the thinking that the male body is a stronger body, that it’s a more capable body, while a female body is a softer body and perhaps people feel less threatened.

There's an ongoing dialogue about male versus female in the robotics world which slowly expands to alternative approaches. I want to believe that as we evolve as society our approach to future technologies need not be bound to human and subsequently gender representations.

I am looking forward to creative machines, that are not only useful, but also interesting. If we just keep it to the current male vs female paradigm, we exclude all the other possibilities of representation or non-representation of something different, something that is useful and engaging at the same time.

Mari Velonaki is a Professor of Social Robotics at UNSW Faculty of Arts, Design & Architecture. She is the founder and director of the Creative Robotics Lab and the founder and director of the National Facility for Human Robot Interaction Research (UNSW, USYD, UTS, St Vincent’s Hospital).