OPINION: This exhibition is not just about art, it is about us: the land, the sea, our ancestors.

Those words were spoken by Waka Munungurr, ceremonial leader and senior custodian, Djapu clan, at a preview viewing of the Yirrkala Drawings at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. These remarkable works on paper were presented to anthropologists in north-eastern Arnhem Land in 1947. They are on display at AGNSW until February 23, 2014 – alongside a stunning cluster of contemporary larrakitji (hollow log coffins), created by descendants of the original Yirrkala Drawings’ artist.

In this exhibition, the contemporary and the historic face each other. For the artists and their descendants these works are title deeds to their country, the surrounding sea, embedded with their physical and cultural DNA.

It’s an engaging legacy for future generations of Yolngu, the Indigenous people of north-eastern Arnhem Land – with Balanda (non-Indigenous people) also able to gaze upon these luminous, multi-faceted cultural gems.

Garma in Gulkula

A decade ago, I attended the annual Garma Festival, a celebration of Indigenous cultural traditions and practices held at a site on Rirratjingu/Gumatj clan country known Gulkula in the Northern Territory.

The warm, humid, tropical landscape is stunning and a monsoonal climate during part of the Wet Season often brings cyclones in from the Arafura Sea to the northwest and the Gulf of Carpentaria to the east.

The people of this region refer to themselves collectively as Yolngu (which translates directly as people) with the main clans being the Rirratjingu, Djapu, Marrakulu, Ngaymil, Galpu, Djambarrpuyngu, Marrangu, Datiwuy and Djarrrwark of the Dhuwa moiety; and the Gumatj, Dhalwangu, Manggalli, Madarrpa, Munyuku, Warramirri, Wangurri, Gupapuyngu and Ritharrngu of the Yirritja moiety.

Revered cultural leader and artist Mungurrawuy Yununpingu (Gumatj clan, Yirritja moiety) represented this sacred site in his bark painting Gulkula in 1967, describing Gulkula as a place where Yolngu have danced “from the beginning”, an all-encompassing (philosophical, physical, cosmological, theoretical) place of all-time referred to by Yolngu as Wangarr.

Gulkula, a ceremonial ground from time immemorial, is set in a stringy-bark forest atop an escarpment of trees.

Each August during part of the dry season the site buzzes with cultural energy resonating throughout Garma, in concert with native honeybees hovering around the flowering Gaydaka – grey stringy-bark – in an echo of the site’s ancestral honey bees being observed by the Ancestor Ganbulapula in the Wangarr.

Encountering Gulumbu Yunupingu in Yirrkala

It was on this site in 2003 that I was first introduced to the work of Mungurrawuy’s daughter, the late Gulumbu Yunupingu (c. 1945-2012), a cultural leader in her own right.

She was best known at that time for being the guiding force behind translating the Bible into Gumatj in 1985, a task she had assumed over the previous quarter century. As a teacher’s aid and health worker, she established her Dilthan Yolngunha healing centre where she melded European and customary, bush medicine and healing. Within months this would change and she would be known foremost for her sublime art.

In the twilight I walked up to the edge of the escarpment, slightly away from the main ceremonial ground and was transfixed by the sight of a group oflarrakitj (hollow log coffins), arranged in a circle embedded into the sand. My eyes were immediately drawn to a larrakitji on which was finely painted a constellation of overlapping stars, seeming to pulsate in the dying light of day.

I tracked down the name of the then relatively unknown artist at Buku-Larrnggay Mulka centre in nearby Yirrkala. The centre is rightly lauded as one of the most significant and successful community-owned and operated arts/cultural operations in the country.

The Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

It is the cultural wellspring of the community, not only a contemporary art space attracting private collectors and public institutional representatives from around the country and overseas, but most importantly, the repository of communal and collective knowledges handed down for thousands of generations.

Opened in 1988 Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre expanded from Buku-Larrnggay Arts, established in 1976 after the withdrawal of the Methodist Overseas Mission from Yirrkala, coinciding with the burgeoning national Land Rights and Homeland movement.

The Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre houses a core body of works compiled in the 1970s, while at its heart/soul are the Message Sticks from 1935 and the 1963 Yirrkala Church Panels.

Many would also be familiar with the historic 1963 Yirrkala Bark Petition, now housed in the Parliament House Library collection in Canberra.

But apart from those at Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, the broader Yirrkala community and a select few in the disciplines of visual and social anthropology and Indigenous art, very little was known about the astonishing Yirrkala crayon and pencil drawings on butchers paper, which were commissioned by pioneering anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt during a research trip to Yirrkala in 1946-7.

The Yirrkala Drawings

It is a selection of these works that are on display at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, alongside a cluster of contemporary larrakitji, created by descendants of the original Yirrkala Drawings’ artists.

The Berndts spent five months onsite working closely with senior cultural leaders and custodians, most especially under the tutelage of Wonggu Munungurr (c. 1884-1958, Djapu clan, Dhuwa moiety), among a broader group of 27 artists and cultural leaders including Mungurrawuy Yunupingu, Narratjin Maymurru (c. 1916-81, Manggalili clan, Yirritja moiety) and father and son, Mawalan Marika (c. 1908-67, Rirratjingu clan, Dhuwa moiety) and Wandjuk Marika (c. 1927-87).

To give a sense of the astonishing cultural changes experienced by the Yirrkala artists, consider Munungurr’s life experiences: his life spanned confrontational late 19th century colonial contact, fruitful and mutually respectful exchanges with the Bugis people and Macassan traders from Sulawesi, through to early 20th-century interactions with explorers, clashes and negotiations with Japanese fishermen, police and other government officials, the warily accepted arrival of Christianity via the Methodist Church in the mid 1930s, further conflict with Japanese soldiers during the second world war – and then the exchange with the Berndts a year or so after the war.

The Berndts collected an astounding 365 drawings on paper, created by the 27 artists over five months. Now acknowledged as exceptional cultural treasures, the drawings were initially considered as a research adjunct, albeit with accompanying detailed catalogue notes, to support the extensive collection of bark paintings.

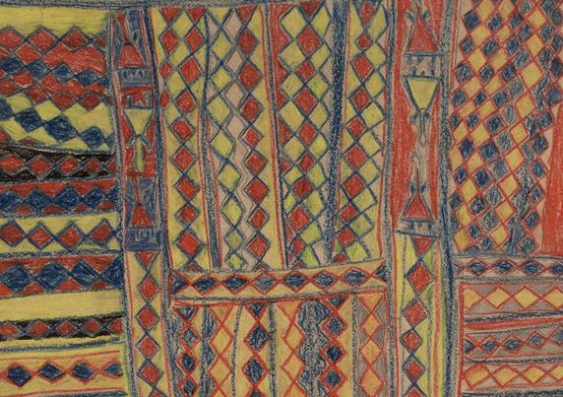

At Ronald Berndt’s request his father sent the materials up to Yirrkala from Adelaide, making a somewhat arbitrary choice of brightly coloured wax crayons - red, blue, green and yellow, with white chalk borrowed from the schoolroom.

Although not what the artists were used to working with – white pipe clay, black manganese, yellow ochre, which is heated to create red pigment – their creations showed great mastery, and the artists achieved the desired fine lines through the addition of lead pencil.

Yirrkala at AGNSW

Now, almost 70 years on, a significant selection of these works on paper can be seen by a fortunate public audience in the Yirrkala Drawings Exhibition.

The exhibition is a project that has been years in development, guided by the determination of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka’s Co-ordinator, Will Stubbs, in close and intense consultation with descendants of the artists, many contemporary artists of increasing national and international renown whose visual repertoire extends on their fathers’ profound cultural knowledge seven decades before. In conversation with me, Stubbs compared the drawings and the profound wisdom they represent with illustrated chapters from the Bible or Qu’ran.

Buku-Larrnggay Mulka worked closely with the Berndt Museum, the University of Western Australia and the Art Gallery of New South Wales (which published the wonderful accompanying exhibition catalogue, which includes essays by John E. Stantonfrom the Berndt Museum, Yirrkala scholar Professor Howard Morphy, Buku-Larrnggay Mulka associate Andrew Blake, and an illuminating foreword by Cara Pinchbeck, Curator of Aboriginal Art at AGNSW).

The drawings from that long-ago research trip now on display are literally brilliant: a combination of the dazzling palette of strokes and hatching, as vivid today as when first created. They reveal cultural interactions with visiting Macassan traders and their customs, and represent elements of intricately detailed, highly complex Yolngu knowledges, reflected and resonating down the decades and into the future.

Brenda Croft is a Senior Research Fellow at the National Institute for Experimental Arts, COFA.

This opinion piece was first published in The Conversation.