Bilingual Aussies are better spellers

Bilingual Australians are better spellers than monolinguals but they struggle to understand some spoken English, according to the first language study of its kind.

Bilingual Australians are better spellers than monolinguals but they struggle to understand some spoken English, according to the first language study of its kind.

Bilingual Australians are better spellers than monolinguals but they struggle to understand some spoken English, according to the first language study of its kind.

A mischievous professor occasionally wrote correspondence seeking independent separate accommodation to be made available immediately for his paraphernalia.

If you're an English-speaking Aussie, you've only got half a chance of spelling that sentence correctly because it contains so many hard-to-spell words.

But if you're also fluent in another language - such as Vietnamese or Mandarin - you're much more likely to get it right, according to an unusual new study.

UNSW researchers have found that while bilingual Australians may struggle to understand some spoken English, they tend to be better spellers than monolinguals.

The finding has implications for the training, education and workforce development sectors, given that one in five Australians are bilingual.

The study reveals that bilingual ethnic Chinese and Vietnamese Australians who had learnt English as a second language were better at spelling hard-to-spell English words than monolingual Australians. Chinese bilinguals spelt 65 percent of words correctly, compared to Vietnamese bilinguals (60 percent correct) and monolinguals (52 percent correct).

The two Asian bilingual groups were better at spelling difficult-to-spell words such as: accommodation, separate, professor, occasionally, immediately, correspondence, paraphernalia, mischievous, and independent. However, they had a poorer understanding of spoken English, particularly new and unfamiliar words.

The findings come from a study of nearly 200 university students and recent graduates who were born in Australia, or who arrived here by age five. All the participants used English as their dominant language but acquired it as their second language. They tend to use their first language only at home.

Bilinguals who acquire their second language "late" - after about age 12 - are usually less proficient than monolinguals at using the sounds (phonemes) of that language, according to PhD psychology student Minh Nguyen-Hoan, who led the study under the supervision of Professor Marcus Taft.

"Adult bilinguals who acquire their second language before about six years of age tend to be more native-like in their use of English than late bilinguals, but they still struggle with some speech sounds," says Minh, who didn't speak English himself until he started pre-school.

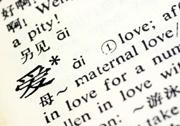

The "good spelling" effect was most evident among those participants who knew how to read Chinese, according to Minh. "Learning Chinese characters requires rote memory because the relationship between a character and its pronunciation is largely arbitrary, unlike alphabetic scripted words where the individual letters correspond to individual sounds.

"Reading Chinese requires a person to remember the shape and look of a character. So, we suspect that the rote memory required to learn to read Chinese encourages better visual memory and this in turn facilitates better spelling in English."