How did we become so indifferent to human life?

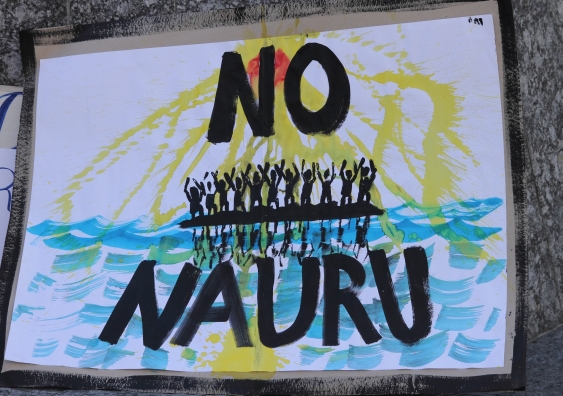

The muted reaction to reports of abuse of asylum seekers in Nauru suggests many people have become immune to evidence about the harm experienced by refugees, writes Jane McAdam.

The muted reaction to reports of abuse of asylum seekers in Nauru suggests many people have become immune to evidence about the harm experienced by refugees, writes Jane McAdam.

OPINION: The release this week of 2000 incident reports from the immigration detention centre in Nauru sadly vindicates the consistent accounts of mistreatment already on the record – by refugees, former staff, UNHCR, the Australian Human Rights Commission and other independent observers. Notwithstanding the concerted political attempts to discredit the credibility of their message (and their messengers), the systemic abuse documented in official reports shows the dysfunction and distorted reality that has become part and parcel of Australia's offshore processing regime.

Less than 24 hours after footage was screened of the ill-treatment of youth in the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre, our Prime Minister called for a Royal Commission, backed by overwhelming public support. Yet, despite years of reports, testimonies and secret footage from Nauru (journalists are banned from the facilities), neither the government nor the public shows similar concern.

It seems that many of us have become immune to evidence about the harm experienced by refugees. Some of that harm is physical – including sexual assault and child abuse. Much of it is psychological – and at rates that are off the scale. Children feature disproportionately in the reports – over 51 per cent of cases – even though they comprised only 18 per cent of refugees in detention at the time. The long-term, and in some cases, permanent damage compounds the trauma many have suffered at the hands of persecutors at home. So why the lack of concern?

Part of it is linked to the concerted crusade to depict asylum seekers as illegal. This old red herring taps into some visceral fear in our island mentality about invasion by sea. The reality is that everyone has a right to seek asylum from persecution. This is why the Refugee Convention says it is unlawful for governments to penalise refugees who show up without a visa. It's also why the treaty on people smuggling says that a refugee's right to find safety must be safeguarded above all else.

Ensuring that a child's best interests are a primary consideration is not a choice, but an obligation. Ensuring that no one is subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment is not a social nicety, but a fundamental legal duty.

In two weeks, it will be 15 years since the Norwegian freighter, the Tampa, responded to Australian Maritime Safety Authority's call to aid of 438 asylum seekers in peril. The Australian government refused to let them disembark, and the standoff ultimately marked the first step in what was to become the "Pacific Solution" – refusing to let asylum seekers apply for protection in Australia, and the creation of offshore processing.

It is worth remembering that the UN Refugee Agency subsequently awarded the captain and crew of the Tampa the Nansen Refugee Award – the highest honour that be bestowed by UNHCR – for their "personal courage and unique degree of commitment to refugee protection".

The ill-treatment of refugees on Nauru is not only morally wrong, but it violates countless principles of international law. Ensuring that a child's best interests are a primary consideration is not a choice, but an obligation. Ensuring that no one is subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment is not a social nicety, but a fundamental legal duty. Australia cares much about international law when it involves whales or our territorial sea, yet seems largely indifferent when it involves people's lives.

The harm experienced by refugees on Nauru is taking place on our watch, and under our legal responsibility. This is not just Nauru's problem – it is ours, too.

Trump's call to build a wall to keep out immigrants is often mocked. Yet, Australia has already constructed its sea-wall, which rises higher with each new piece of Orwellian legislation.

Jane McAdam is Scientia Professor of Law and Director of the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at UNSW.

This article was first published in The Sydney Morning Herald.