What we can learn from the Warren Buffett of the web

Masayoshi Son's business model offers valuable lessons on how to make it in the high stakes world of tech, writes Paul X. McCarthy

Masayoshi Son's business model offers valuable lessons on how to make it in the high stakes world of tech, writes Paul X. McCarthy

OPINION: Softbank’s founder and chief executive Masayoshi Son, or “Masa” as he is known outside Japan, has often been called “the Bill Gates of Japan”. Today, I suggest a more appropriate moniker may be the Warren Buffett of the Web.

Strategic and with an eye for long-term value, Masa has led Softbank to become an online giant now valued at more than $US100 billion ($A130.44 billion), as the result of many investments, joint ventures and strategic decisions – and not simply from the proceeds of one dominant network business.

Therefore, Softbank’s business model can offer valuable lessons for how to make it in the high-stakes world of tech. And although his recent investments in WeWork have seen some industry observers questioning his fiscal wisdom, the evidence suggests that it too will ultimately reap rewards.

Masa is a Japanese businessman with Korean ancestry who studied Economics at the University of California, Berkeley in the late 1970s. While still a university student, Son brought Japanese coin-operated arcade games such as Space Invaders, Scrambler and Pacman to California.

His approach to his first arcade games business reveals his Buffet-like mind. Atsuo Inoue’s biography explains how Son recorded a log of daily cash received for each video game machine and its trends. Some games were popular at the beginning and quickly tapered off, while others were perennial hits. Analysis of this data helped him decide which machines to keep and which to replace in order to optimise daily returns.

In many games like chess, the centre of the board is prime real estate. Anyone who has played squash or racquetball also knows that positioning yourself at the central ‘T’ puts you at a distinct advantage. Similarly, with many multi-sided marketplaces, being in the centre as the “market maker” is often the most powerful and stable position.

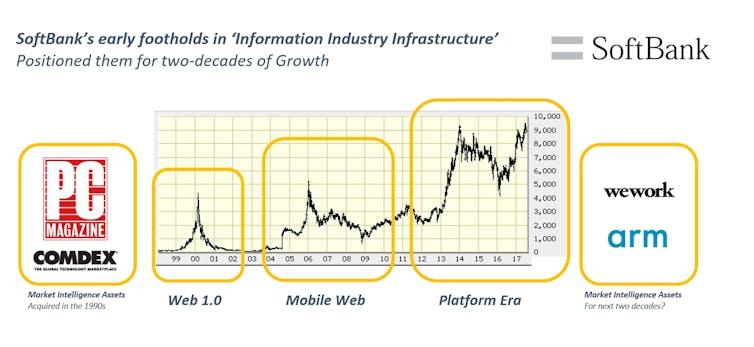

After university, Masa returned to Japan to create Softbank in 1981. He got his start creating packaged wholesale software distribution businesses but soon expanded into people-network businesses such as technology magazine publishers (Ziff Davis) and events (Comdex) that connected many parts of the industry together. He called this information “industry infrastructure”.

Softbank began in technology magazine publishing, as well as hosting large trade shows for the tech sector. They did this first in Japan, but in the 1990s expanded into the US via large acquisitions including the biggest trade show (Comdex) and technology magazines including PC Week and many other titles.

This really put him in the “centre of the squash court”.

In the earliest days of the web, Masa invested in some 800 companies during the dot-com boom, including well-known brands like Yahoo. For three days Masayoshi Son was the richest person in the world – richer than Bill Gates.

But this was short-lived, and in the dot-com crash of 2000 his stock fell 99%, costing him more than US$60 billion ($A78.44 billion) in personal wealth. But despite the crash, one of his investments in 2000 was a $US20 million ($A26.1 million) placement in Alibaba. That stake is now valued at around $US90 billion ($A117 billion).

Masa thinks his largest investment to date, the acquisition last year of UK Chip designer ARM for £23.4 billion ($A40.1 billion), will one day become more valuable than Google. As the Internet of Things takes off and chips become a part of everything, the dominant position of ARM will pay off big time.

In 2017 Son has created an extraordinarily ambitious $US100 billion ($A131 billion) Softbank Vision Fund that is aligned to his own personal vision. It is a three-century plan to invest in technology to help protect people from many of the worlds physical problems and dangers – such as autonomous vehicles that, once operational, promise to save millions of lives each year from avoided road deaths.

Already the fund has attracted $US1 billion ($A1.3 billion) each from Apple and Oracle founder Larry Ellison. After one 45-minute meeting with a Saudi Crown Prince, he attracted a commitment to co-invest $US45 billion ($A59 billion) with the plan to turn that investment into a trillion dollars through far-reaching investments in Artificial Intelligence, space exploration and the Internet of Things.

The announcement in August that Softbank has invested $4.4 billion in co-working space leader WeWork to help fund their ambitious global expansion has met with mixed responses from the media with the Wall Street Journal’s Eliot Brown calling it “A $20 billion Startup Fueled by Silicon Valley Pixie Dust” and Author of bestselling book The Four, Professor Scott Galloway calling it overvalued in May prior to the Softbank Investment.

Some such as Neil Murray, commentator on the Nordic startup and technology scene think Softbank’s investment is overpriced and it wildly overvalues the company – whose nearest competitor the more traditional serviced office provider IWG (formerly Regus) doesn’t enjoy such a generous valuation from the market.

However, as WeWork is now a trusted partner to thousands of the fastest growing new businesses in the world, Softbank may well have again have bought themselves front row seats for a whole new generation of high-growth investee companies.

![]() Masa’s approach is a lesson to all in business how a strategic approach to technology investments with a long view and a portfolio approach – some of which position the investor for future investments – can pay off handsomely.

Masa’s approach is a lesson to all in business how a strategic approach to technology investments with a long view and a portfolio approach – some of which position the investor for future investments – can pay off handsomely.

Paul X. McCarthy is an Adjunct Professor at UNSW.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.