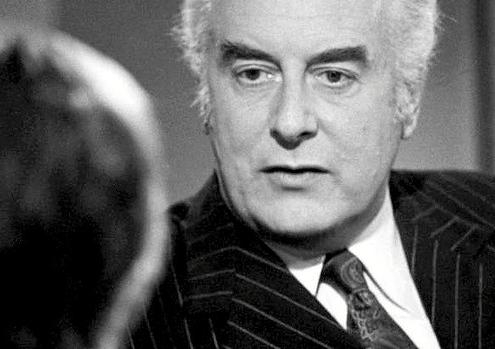

Thanks for the confidence, Gough

Gough Whitlam made us confident. Confident to be Australian, confident to be ourselves and confident to take on the world knowing who we are, writes Tim Harcourt.

Gough Whitlam made us confident. Confident to be Australian, confident to be ourselves and confident to take on the world knowing who we are, writes Tim Harcourt.

OPINION: “Where were you when Gough was sacked?” This of course refers to Remembrance Day, 11 November, 1975, when the elected prime minister Gough Whitlam was sacked by Governor-General Sir John Kerr in cahoots with the leader of the Opposition, Malcolm Fraser.

For Australians, it’s a bit like the question, “Where were you when Kennedy was shot?” Of course I mean US President John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK), when he was shot in Dallas on 22 November, 1963, but apparently in Melbourne where Graham Kennedy hosted the very popular TV program “In Melbourne Tonight” the news “Kennedy is shot” caused some viewers to reply: “Well I guess that gives Bert Newton his big chance.”

On the day of what is now known as “The Dismissal”, I was at Cubs. After all I was 10. And I was so angry about Gough being sacked, I said to the Akela we should take down the portrait of the Queen and put one up of Gough Whitlam in her place. Gough said “maintain the rage” and my father had spoken at a protest rally that day, so as 10-year-old, this was my response to the call.

But while Gough said to maintain the rage, after the elections defeats of ‘75 and ‘77 the ALP did actually get down to some serious policy work – particularly in economics – with the Committee of Inquiry chaired by John Button. So by the time Labor returned to office in 1983 with Bob Hawke, we had the Prices and Incomes Accord with economic management at the centre of the Hawke Government. There was a trained economist in Hawke, another in his fellow ACTU research officer in Cabinet Ralph Willis, and an energetic reforming treasurer by the name of Paul Keating. And the rest is history.

Of course Gough had a very successful post prime ministerial career and I had the opportunity to work with him as part of the Whitlam lectures series for Trade Union Education Foundation (TUEF) particularly with his work on China and the Asia Pacific region. It was a great honour and it was also hilarious being Gough’s chaperone around various cities. He would often enter the gentlemen’s bathroom, approach the urinal, and when the occupants said “my god it’s Gough” he’d say “make way for the great man” with heavy irony. Also when he met someone who had migrated to Australia, and if they came from anywhere Spain, Greece, Italy, Chile or China, he’d know all about the history of their home village, their surname, and so on, which delighted them (and amazed me).

However, I have a confession to make. As an economist albeit from family of true believers I was firmly in the camp of “Gough doesn’t know any economics and that’s why he lost".

‘What Gough knows about economics…’

Several Labor leaning economists – mainly from Adelaide – my father Geoff Harcourt, Eric Russell (father of Don Russell), Barry Hughes and Philip Bentley all tried in the late sixties and early seventies to get Gough interested in economics. Geoff, who was the economist on the ALP Committee of Inquiry, found Bill Hayden as a trained economist much easier to work with.

Of course, Gough did have Fred Gruen (father of the distinguished economists David and Nick Gruen) as an adviser, but his focus was clearly elsewhere. In fact, when I interviewed Bob Hawke about this period he said to me: “What Gough knows about economics you could write on the back of a postage stamp and still have some room to spare.” Hawke as ACTU and ALP President had wanted Gough to focus more on economics, and just before the 1972 election, at the ALP federal executive, he said: “Gough… you’re going to do some great things in government in the social welfare area and internationally… but your government will live or die on how you handle the economy.”

Gough didn’t have the passion for economic management that he had in other areas of “the programme” like foreign policy, social reform, education, the status of women, indigenous affairs and the arts and it showed in areas of macroeconomic management (although this was true of all OECD governments after the OPEC Oil shock and true of the Fraser-Howard years too as they struggled with the recession of their period of office). Gough did have some microeconomic policy achievements in anti-competition reform, and productivity boosting reforms in the labour market by implementing equal pay for women and increasing opportunity in education.

Then there were the across-the-board tariff cuts – judged to be too harsh and too quick (“the short sharp shock”) and more designed as an anti–inflationary tool given the impact of high import prices on inflation. The implementation was all wrong too. As Bob Hawke recalled: “I think Fred Gruen said to him we should reduce tariffs and he said ok, ok.” And that was it.

Gough’s former chief of staff John Menadue said that Gough did have a view of structural reform in Australian industry and quipped rather harshly about the textile clothing and footwear (TCF) industries: “We’ve fucked those industries and that’s a good thing.” But overall the short sharp shock approach was not economically feasible and was politically disastrous, with the result being a harsh swing against the government in the Bass by-election.

In fact the experience led the way to the gradual, strategic approach to trade and industry policy by the Hawke Government, with the phases of tariff reductions of the Button Plans, in cars, steel and TCF. After the hurried approach to public policy by the Whitlam Government, the Hawke Government changed the policy, the pace, and the process in everything from tariffs to industrial relations. And of course they had the co-operation of the trade unions through the Accord process. The ACTU was determined not to make the same mistakes in the Hawke era that had occurred in the Whitlam era.

In fact, the great irony was that Gough’s economic legacy was in foreign policy.

The first wave of the Asian Century

Gough’s decision to recognise China did more for the Australian economy than many other more heralded changes in the economic policy sphere. When you think about it China was a risk. Especially as Gough went to China as opposition leader before he formed government.

Here was Gough in 1971 on the cusp of being the first Labor prime minister since Ben Chifley in 1949 (the year the Chinese communists took power) breaking bread (or rice) with a Communist state. And he took some heat from it from the McMahon government, for about a week until it was revealed that Henry Kissinger had been in Peking (now Beijing) too paving the way for US President Richard Nixon to recognise China. And of course, after winning the 1972 election Gough returned to Beijing as prime minister in 1973 and he and Margaret were feted as great friends of China. It was a triumph.

When talking to Gough and later John Menadue, it was explained to me that the decision to recognise China was part of the Whitlam vision to engage Australia more comprehensively with the Asia Pacific region. Gough and South Australian Labor Premier Don Dunstan had fought hard to get rid of the White Australia Policy from the ALP platform and took the principled view that if you wanted to trade and invest with people, or sell education services to them you shouldn’t prevent them from immigrating because of the colour of their skin or racial origin. It was part of the big picture, diplomatically to engage with Asia, and to allow exchange of ideas, art and culture as well as good and services. To feel more confident in the Asia Pacific region, particularly after the difficulties of the Vietnam war.

In some ways it was one of the “waves” of Australia’s engagement with the Asian Century. We had the Country Party Deputy Prime Minister and Trade Minister “Black Jack” McEwen signing a deal with Japan in 1957, Gough in China in 1971-3, and then the Hawke-Keating reforms of 1983. Now, in 2014 both sides of politics take Australia’s engagement with Asia as a given and it’s largely bipartisan. And China’s our number one trading partner worth almost A$142 billion. But it wasn’t in 1971 when Gough took the plunge. China was a risk. It was a bold and confident move.

Gough Whitlam made us confident. Confident to be Australian, confident to be ourselves and confident to take on the world knowing who we are. He helped modernise Australia and enhance our place in the world. Now when I travel to Beijing, (or even Berlin or Buenos Aires) I think of that Whitlam confidence. It could well be that Gough’s foreign policy adventure provided us with one of our greatest economic legacies after all.

Thanks Gough.

Tim Harcourt is the JW Nevile Fellow in Economics at UNSW Business School

This article was first published in The Conversation.

Wikimedia