UNSW graduate personifies the spirit of the Invictus Games

Benjamin Farinazzo has his sights set on rowing and powerlifting glory after suffering PTSD following military service in East Timor.

Benjamin Farinazzo has his sights set on rowing and powerlifting glory after suffering PTSD following military service in East Timor.

As a rower and powerlifter, Benjamin Farinazzo is the picture of strength. But as he raises the barbell at this year’s Invictus Games in Sydney, spare a thought for the weight that he’s carried on his shoulders since he served in the military.

Farinazzo, a UNSW Canberra graduate, describes his service in East Timor as the highlight of his military career, but it also left him with psychological scars.

“I had the very fortunate opportunity to work closely with the East Timorese people,” Farinazzo says. “It was such a deep human connection I had with those people.”

Farinazzo was in East Timor in 1999, when the Suai Church massacre occurred. Up to 200 people, seeking refuge in the church were killed by the militia. He had the heart-wrenching task of helping locals, many of them children, find the bodies of their loved ones.

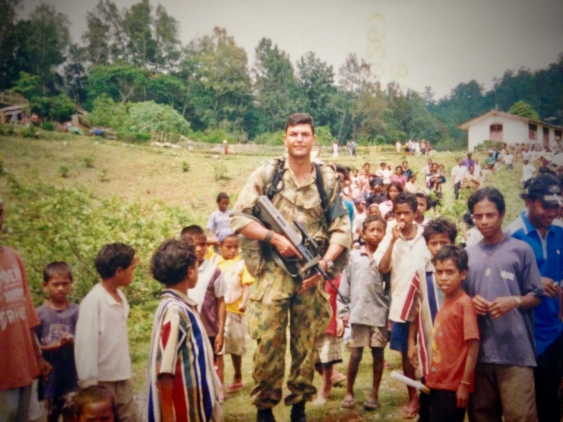

UNSW Canberra graduate Ben Farinazzo during his time serving in the military

“That had a deep emotional impact on me,” he says.

“I knew it did at the time, but I didn’t realise the extent to which it had an impact on me. Of course, I came back and bottled it away and got on with my life, but over time that wound continued to fester, to the point where I tried so hard to block those emotions.

“At the same time, you tend to block the other emotions such as joy and happiness, so you don’t feel anything anymore. That led me to a point where I started to consider what life was all about.”

Eventually, the sleep difficulties, nightmares, mood swings and irritability caught up with him.

“You have all these different strategies that you put in place, but unless you address the root cause of it and seek professional help, it can tear away at you,” he says.

Farinazzo visited an empathetic doctor, who had her own experience as a veteran in Rwanda. He remained stoic even after the post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis.

“I was like: ‘Alright, what is the three-step strategy that I need to get on top of this thing?’” he recalls. “And she said: ‘Well, it’s a bit more complicated than that’.

“I said: ‘Well, I guess I’ll just see it as a broken arm or something, I’ll just look after it and get on with life.’

“She said ‘Ben, stop. It’s not like that. It’s more like cancer. If you don’t address this thing properly, you will die from it.’ And that was pretty hard.”

Farinazzo sought help, but he was far from out of the woods. While he was being treated, he had a mountain bike accident and broke his neck and back in several places.

“So, I was walking through the valley of the shadow of death and then I well and truly hit rock bottom.”

Through treatment, Farinazzo learnt that his vulnerability could be his saving grace. His first step to recovery was learning to open himself up to people.

Once he opened up about his battle with mental illness, he learnt that he wasn’t alone. He discovered friends and colleagues who were facing their own battles with PTSD, anxiety and depression.

“It’s amazing that once you start becoming open about it, when you start expressing how you’re genuinely feeling, it gives people the confidence and the courage themselves to be open and to be authentic about how they’re feeling, their emotions and the impact it’s having on their lives,” he says.

As part of his recovery, Farinazzo turned to rowing. When he heard about the Invictus Games, it gave him something to aspire to. He decided once he was capable of being out of hospital for at least 12 months he would submit an expression of interest.

Ben Farinazzo trains for the rowing event ahead of the 2018 Invictus Games in Sydney

He achieved that milestone at the end of last year.

“Then the world changed,” he says.

“As soon as I found out that I was part of the potential selection squad, a fantastic opportunity opened up to then join other potential athletes and to compete at the various selection camps.”

Farinazzo was selected to represent Australia in rowing and powerlifting at this year’s Invictus Games, which start on October 20 in Sydney.

The word ‘Invictus’ is Latin for ‘unconquered’, reflecting the story and the spirit of competitors such as Farinazzo.

“In my experience connecting through the healing power of sport has been invaluable,” he says.

Farinazzo’s renewed strength means the weight on his shoulders no longer feels so heavy.

Ben Farinazzo trains for the powerlifting event ahead of the 2018 Invictus Games in Sydney

“The spirit of Invictus is about celebrating the unconquerable human spirit and to me that means being able to stand up authentically, being vulnerable and saying ‘this is who I am – faults, smiles and all’,” he says.

“It’s that wonderful feeling of being inspired by such a great community of athletes around you from around Australia, around the world and everyone in the stands. I can’t wait.”

UNSW Canberra is a Premier Partner and the Official University Partner of Invictus Games Sydney 2018. The Games are an international sporting event for wounded, injured and ill veteran and active service personnel, and highlight the power of sport to inspire recovery, support rehabilitation and generate a wider understanding of those who serve their country.