New South Wales is on a knife edge after recording more than 150 COVID-19 cases over the last 14 days, a worrying sign the situation could spiral out of control.

The wide geographic spread is of particular concern, as it would rule out ring-fencing as a possible approach to containing the spread of the virus.

It comes as the Queensland government has closed its borders to arrivals from Greater Sydney after declaring the area a hotspot. People returning to Queensland from this area must quarantine in hotels for two weeks from 1am Saturday August 1.

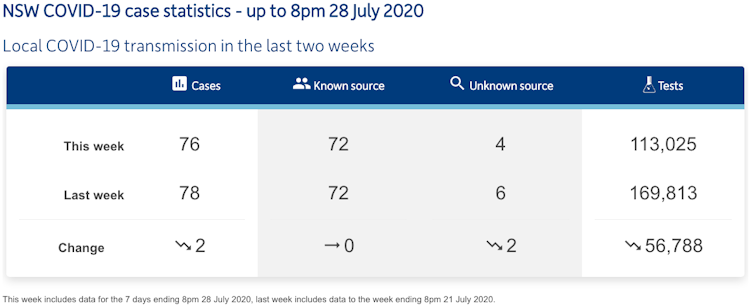

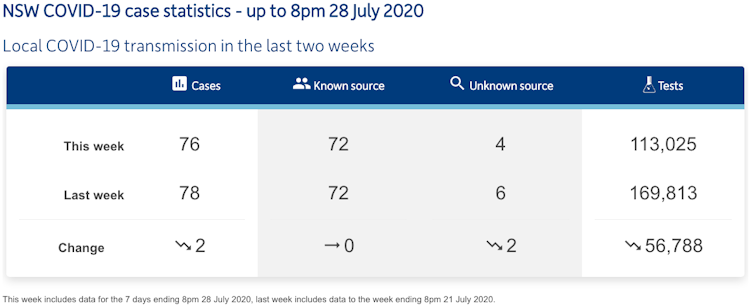

NSW Health

NSW in the ‘red-zone’

The state recorded 19 new cases in the 24 hours to 8pm on Tuesday, but watching the fluctuations in daily numbers doesn’t necessarily paint an accurate picture of the spread of this virus.

It’s better to look at rolling 14-day cumulative cases, meaning the last 14 days of new cases added together, which represents roughly two incubation periods.

My analysis of the data suggests when cases reach 100 over 14 days - the “red zone” - then an outbreak becomes very difficult to control. This happened in Victoria on June 18, before cases skyrocketed and a second lockdown was called for July 8.

Over the last fortnight, NSW has recorded at least 154 new cases (minus international arrives in quarantine), which is very concerning.

NSW had previously been tracking very well in managing the virus, before cases imported from Victoria started several chains of transmission, including the Crossroads Hotel cluster.

The new cases are very spread out

Another concern is that many of the new cases are very spread out geographically. We’ve seen new cases in central Sydney, Casula and Bankstown in the city’s west, Harris Park in the north-west, and also several hundred kilometres south in Bateman’s Bay.

This spread rules out ring-fencing as a viable control method. Ring-fencing is a strategy to enforce stricter measures in a very defined location to prevent spread within the broader community. It has been used successfully in parts of Beijing, and in Melbourne’s north-west prior to the lockdown across metropolitan Melbourne.

What else can be done?

NSW authorities should consider strongly urging Sydneysiders to wear face coverings on public transport. Masks have been shown to offer protection against both getting and spreading the virus.

The state also needs additional infection control measures in aged care. We can see the devastating impact of COVID-19 spread currently occurring in some aged care homes in Victoria. All staff should be wearing face masks or shields, and should be tested regularly for COVID-19, both of which are cost effective control methods.

Effective messaging is also key, particularly when aimed at young people, given over 40% of cases in Victoria are in people aged 20-39 years.

The government needs to disseminate public health messages on platforms that younger people typically use, perhaps by reinforcing the notion we all share responsibility for ending this virus.

Another risk that must be managed is public health messaging fatigue. Authorities need to help the public become resilient to changes in rhetoric as scientific knowledge about the virus advances.

What to look out for

Over the coming days and weeks, NSW health authorities must keep an eye on the ages of people testing positive.

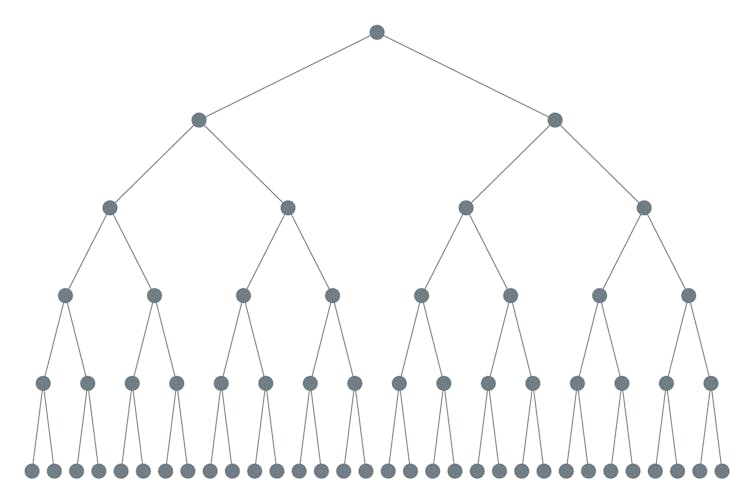

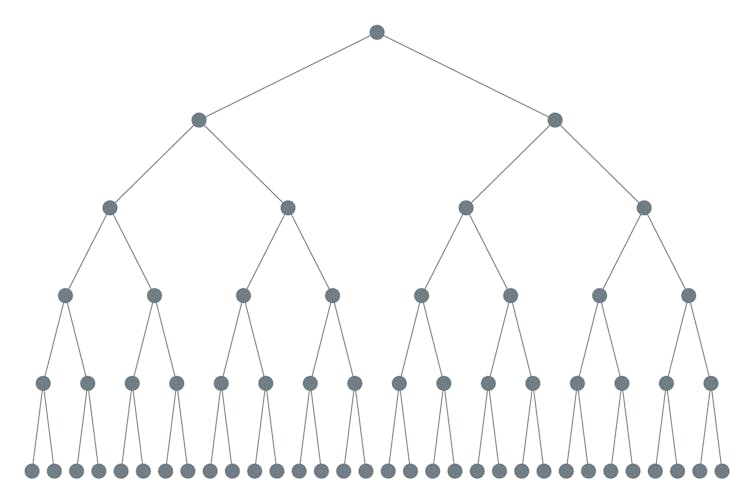

Younger people tend to have many more social connections, sometimes up to 20 close contacts in the infectious period. This means contact tracers need to work extra hard to locate and isolate all close contacts.

One person can result in more than 50 infections, where each person infects two others. The more social contacts you have, the greater the potential spread. Shutterstock

I would be very worried if cumulative cases over a two-week period continue trending upwards and if many of the new cases were young people.

If even a handful of close contacts are not identified, they could go on to infect others and start even larger chains of infection.

One cause for hope is that rates of community transmission where the source of infection is unknown appear to be relatively low, though some cases are still under investigation.

This article is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.

Mary-Louise McLaws, Professor of Epidemiology Healthcare Infection and Infectious Diseases Control, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.