A trend we must reverse

Around 3,000 Australians take their lives each year, a frightening statistic that Black Dog Institute chief Helen Christensen is determined to turn around.

Around 3,000 Australians take their lives each year, a frightening statistic that Black Dog Institute chief Helen Christensen is determined to turn around.

Helen Christensen took up skydiving while in her 20s – leaping out of aeroplanes above Sydney. She vividly recalls her first solo jump: “I remember how powerless and fearful I felt.”

As she jumped into the void that first time without the back up of a static-line safety mechanism, Christensen realised no one was there to help her pull the rip cord. Without the line, she would have to rely on her mental fortitude and composure if she was to reach the ground in one piece. “All of a sudden, I felt incredibly unsafe,” she says.

Today, as a UNSW Scientia Professor of mental health and director of the Black Dog Institute, Christensen is one of the country’s leading mental health experts. And today the rush of powerlessness and fear she felt on that first solo jump remains a visceral insight into how the 3,000 Australians who take their lives each year must feel.

“If we are ever going to reduce the disturbing levels of suicide in Australia, we need evidence-based interventions – we need to provide the mental health equivalent of that static line,” Christensen says.

“Seventy-five per cent of adults with mental illness report an onset of symptoms before the age of 25. That makes mental illness a chronic disease of young people."

Under Christensen’s guidance, since 2012 the Black Dog Institute (‘black dog’ was the term former UK prime minister Winston Churchill used to describe his own depression) has earned a world-class reputation for its pioneering work on ‘e-health’, embracing digital and social media technology to help reach the one in five Australians who are, at any one time, experiencing anxiety, depression or other mental illnesses.

Using apps, Facebook, Twitter and the internet, Christensen and her teams are identifying people who are showing telltale signs of mental ill health, then offering appropriate self-help digital treatments that have been proven to work.

It’s a community-wide, safety mechanism in action and it is attracting attention around the world. “I wish we had a Black Dog Institute in the US,” Dr Tom Insel, a former director of the US National Institutes of Health, recently told a packed audience at UNSW.

“Australia is way out in front here,” Insel said, referring to our rollout of e-health interventions. “In most other places, in the European Union, the UK and the US, we don’t have the public will and the drive to make an impact.”

The focus on young people was crucial. “Seventy-five per cent of adults with mental illness report an onset of symptoms before the age of 25,” he said, “That makes mental illness a chronic disease of young people.”

The trials and pressures of being a teenager are things Christensen clearly remembers while growing up on Sydney’s northern beaches, enmeshed in its surfing culture of parties and drugs.

She has often hinted at a personal reason for her interest in suicide prevention. “Like most of us, I know people – young and old – who have died by their own hand,” she says.

“Even this morning I got a message from a friend saying her husband had died by suicide.”

But the motivation is even more personal still. Christensen reveals something she rarely discusses: she, too, has suffered from mental health problems – and has herself contemplated ending her life.

“It was in 2011,” she says. “I was going through a very hard time. I got to the point where I genuinely believed everyone would be better off if I was dead. It’s hard to explain, but I was convinced it was true.”

But, she says, the feeling was transient. “The next day, I remember thinking: ‘How could I have possibly thought that? And how could I have really believed it?’ ”

Christensen did not act on her suicidal thoughts. “I never got that far. But I certainly felt the hopelessness – that lack of belonging – that people who attempt suicide talk about. And I felt that sense of social isolation, unworthiness and burdensomeness.

“That was a very big learning experience for me. It convinced me that everybody is capable of contemplating suicide under extreme circumstances.”

Did she follow her own advice when she found herself in that position?

Christensen issues one of her frequent and cheerful laughs. “No. I felt I could deal with it myself. Ironic, isn’t it? Here I was – the mental health expert and I couldn’t even see what was happening to me.

“I don’t think I even thought I was depressed. I was working. I was looking after my kids. I thought I was ‘functioning’ … I felt ‘on duty’.” Fortunately, Christensen’s friends weren’t hoodwinked. “They were saying, ‘Don’t you think it’s time you sought help?’”

Australia is a winner in terms of sporting prowess and living standards, but when it comes to rates of suicide, we are a big loser. Professor Christensen addresses UNSW's Unsomnis even in December. Photo: Prudence Upton.

Born in Hay in New South Wales to a banker father and a mother who was a teacher, Christensen and her six siblings moved frequently around the state. After high school at Narrabeen Girls’ High, she went to the University of Sydney, leaving with an honours degree in psychology.

Her first jobs after university were working in TAFE colleges as a counsellor (mainly working in youth depression) and the hospital system, before returning to university to complete her PhD.

In the 1980s, dementia was considered a normal process of ageing but Christensen was interested in why some people lost their memory while others retained it. This remained her primary research interest until the mid-1990s.

By then, Christensen was working at what is now the Centre for Mental Health Research at the Australian National University.

By happy coincidence, the centre was awarded the federal government contract to write the guidelines for diagnosing mental health issues in young people at the same time the internet was being introduced.

“Before the advent of antidepressants, one of the only treatments for depression was cognitive behaviour therapy or CBT,” Christensen says.

“What’s great about CBT is that it doesn’t require a trained psychologist or psychiatrist. There were already self-help books using CBT that had proven to be effective in clinical trials, but the problem was getting the techniques out to the people who needed them.

“Suddenly there was this perfect dissemination tool that could spread information widely and for no or little cost.”

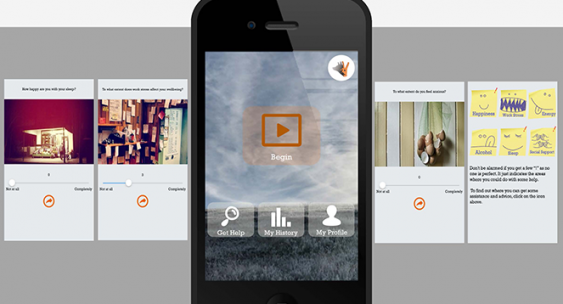

While the internet allowed people easy access to CBT, the “game-changer”, Christensen says, was Apple’s launch of its iPhone in 2007. The age of the smartphone had begun, and with it the proliferation of apps.

“Apps marked a major change in how we thought about reaching the people who most needed help,” says Christensen. “Smartphones and their apps meant anyone could carry their own personalised mental health therapies around with them in their pocket.”

“Rates of suicide among Indigenous children are around three to four times higher than they are among non-Indigenous Australian children. That’s shameful.”

The first standalone Black Dog Institute app, Snapshot, was launched in 2015. Among the suite of apps in progress since then, Black Dog Institute is developing iBobbly – a name derived from a traditional Aboriginal greeting in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. A pilot program of the app in 2013 targeted suicide prevention among Indigenous Australians in the Kimberley, recognising that suicide rates in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are among the highest in the world – and that fewer Indigenous people seek help.

“Rates of suicide among Indigenous children are around three to four times higher than they are among non-Indigenous Australian children,” Christensen says. “That’s shameful.”

The Kimberley pilot proved successful and now further programs are being tested in various Indigenous communities around Australia, funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

The boom in digital engagement also allows research institutes like Black Dog to monitor social websites such as Facebook and Twitter to identify people experiencing mood changes through their altered social interactions. This is done through ‘machine learning’ – mathematical algorithms that decipher mental health signals that would seem meaningless to humans.

Black Dog's first standalone mental health app, Snapshot, was released in 2015. Image: Black Dog Institute

“This is an evolving area,” Christensen says. “There are a lot of technologies out there but the material they gather is not transparent; they have never been demonstrated in clinical groups. That’s our niche.”

These early positive results fly in the face of a common perception that the digital revolution has added to, not reduced, the incidence of mental health problems by introducing cyberbullying and a withdrawal from face-to-face contact. It’s a notion Christensen rejects.

“If you look at all the population surveys, you’ll find that young people are no more – and no less – anxious than they used to be.”

In fact, Christensen says, digital technology has delivered us e-health, offering not only new therapies for age-old problems but new ways to research mental health.

One online program involving Britain’s National Health Service in 2013 was aimed at people who were browsing the web looking for mental health help. When they typed in key search terms, they were randomised to the opportunity to either receive or not receive a web-based mental health program.

“We had 17,000 British people sign up in the first three months,” she says. “We did a similar thing in Australian schools, in GP practices and in Lifeline centres. We were able to use digital technology to conduct research on a huge scale that would previously have been unthinkable.”

Targeting suicide Black Dog Institute chairman Peter Joseph has previously gone on the record to say Australia’s suicide rate could be cut “by a third, if not a half” if these new digital suicide prevention tools received more funding. In 2015, the Paul Ramsay Foundation donated $14.7 million towards LifeSpan, an evidence-based ‘systems approach’ led by the Black Dog Institute that involves the simultaneous implementation of nine proven strategies.“Peter’s an optimist,” Christensen says. “But the LifeSpan program is now in trial and I’m confident we’ll see a 20% reduction in suicides and a 30% reduction in suicide attempts, based on the results of similar large-scale suicide prevention programs overseas and modelling of the impact of each of the separate strategies that comprise LifeSpan.”

It’s a target that we, as a society, desperately need to reach, Christensen says, not just for the personal but also economic cost.

The World Health Organization estimates a quarter of all sick days taken every year are related to mental health issues.

Yet many people are still unconvinced we should be doing more, something that frustrates Christensen. The former skydiver reverts to a language most Australians understand – sport. “Australia is a winner in terms of sporting prowess and living standards, but when it comes to suicide rates we are big losers,” she says.

“Compared to the countries we play professional sport against – like the UK, the Netherlands, Brazil, Germany and Spain – our rates of suicide are worse.

“It is time we turned those statistics around.”

The Black Dog Institute and the Hunter Institute of Mental Health received $5 million in the federal budget to establish a Centre of Research Excellence in the Prevention of Anxiety and Depression.

“The delivery of evidence-based interventions through schools, workplaces and primary health care has the potential to reduce incidence of these disorders by around 20%,” says UNSW Scientia Professor Helen Christensen, Black Dog Institute Director and Chief Scientist.

“This exciting new initiative will help us to develop new prevention strategies and programs, and facilitate the delivery of these strategies to Australians of all ages and backgrounds.”

The NSW-based centre, jointly led by The Black Dog and the Hunter Institute of Mental Health, will support innovative translational research to improve and accelerate the uptake and impact of programs across settings and across communities.

The Hunter Institute of Mental Health Director, Jaelea Skehan says the centre will consolidate and drive world-class activities in prevention.

“The centre includes a multi-agency team of experienced and internationally regarded researchers, educators, communicators and clinicians. This funding will enable us to combine our skills, leverage relationships and build effective and streamlined programs for addressing the risk factors associated with anxiety and depression.

“The centre will place focus on developing accessible and effective programs for those in particular need, including children and young people, targeted workforces and workplaces, families and carers and those living in regional and rural areas.

Funding is expected to commence in late 2017.

– Emily Cook