UNSW researchers identify a target to stop the spread of ovarian cancer

UNSW researchers have discovered a method for disrupting the spread of ovarian cancer, by blocking receptors present on the surface of cancer cells.

UNSW researchers have discovered a method for disrupting the spread of ovarian cancer, by blocking receptors present on the surface of cancer cells.

UNSW researchers have discovered a method for disrupting the spread of ovarian cancer, by blocking receptors present on the surface of cancer cells.

The discovery has raised hopes that a drug that targets the receptors and stops the cancer will soon be developed. The findings are published today in the journal Oncotarget.

With no early detection test and a lack of obvious symptoms in the early stages of ovarian cancer, women are usually diagnosed late after the cancer has spread to other organs in the body. Survival rates for ovarian cancer remain at around 40%, with the disease killing 150,000 women worldwide every year.

Very little is known about how and why ovarian cancer spreads and researchers say this is due, in part, to a lack of understanding of the key genes and molecules that initiate and control the progression and growth of ovarian cancer.

That is slowly changing thanks to pioneering work by researchers at UNSW’s Lowy Cancer Research Centre and their international partners.

In their latest study, the UNSW team found tissue sections taken from ovarian cancer patients had a significantly higher expression of the receptor molecule, Ror2, than tissue sections taken from benign samples.

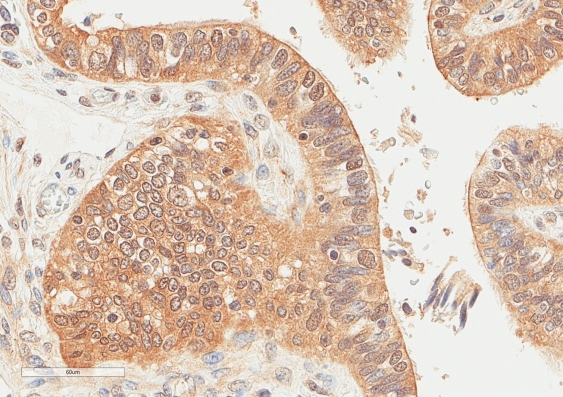

Ovarian cancer cells abnormally expressing the Ror2 receptor (indicated by the brown stain).

It has previously been shown that its ‘sister receptor’, Ror1, is also abnormally expressed in ovarian cancer patients and associated with poor survival.

The team also established that concurrently silencing both receptors had a strong inhibitory effect on the proliferation, migration and invasion of the cancer cells.

Lead author, Dr Caroline Ford, said the discovery is exciting because the receptor molecules identified seem to be expressed universally in all epithelial ovarian cancer patients, not just those with hereditary ovarian cancer.

“Some drugs are showing promise as a treatment for patients with hereditary ovarian cancer, however this group makes up only 15% of all ovarian cancer patients,” said Dr Ford from UNSW’s Lowy Cancer Research Centre.

“For the majority of patients with ovarian cancer, treatment options have made little progress over the past 30 years and there are currently no targeted therapies available.

“Personalised medicine is about targeting treatment to an individual’s particular genetic profile, and unlike other cancer types such as breast, this is still very much in its infancy in ovarian cancer treatment.”

Researchers believe the Ror ‘family’ of receptor molecules are attractive drug targets for three reasons. First, the receptors are not usually present in normal adult tissues which means that any drug therapy will likely have few side effects. Second, the location of the receptors on the outer surface of cancer cells means they can be easily accessed by drugs. Third, Ror1 and Ror2 are a specific type of receptor that controls many other genes, and other members of this specific class of receptors have been successfully targeted for cancer therapies. The cancer drugs Herceptin, Gleevec and Iressa all target receptors of this class.

Separate research has also found that the Ror2 receptor is associated with unfavourable prognosis and tumour progression in cervical cancer. Dr Ford and her team are currently investigating the role of these receptors in endometrial cancer.

The researchers believe the combination of their latest study and others suggests that in all gynaecological cancers both Ror1 and Ror2 may be over-expressed, and is important for disease progression.

Dr Ford believes it is imperative that the relationship of the two receptors is investigated, to further understand their individual and combined roles in the progression and spread of ovarian cancer.

“Once we better understand the roles of these receptors we will be in a position to develop a drug to target these receptors and hopefully halt ovarian cancer in its tracks,” Dr Ford said.

The UNSW study focused on epithelial ovarian cancer which is the most common type making up about 90% of tumours of the ovary. Rarer types of ovarian cancer include germ cell tumours (cancer of the egg making cells of the ovary) and sarcomas.

The research was made possible as a result of funding from the Ovarian Cancer Research Foundation.