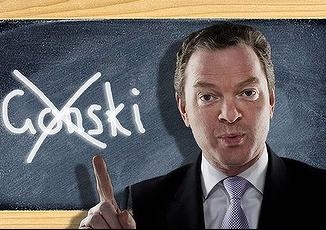

OPINION: Education minister Christopher Pyne has announced the new government will dump the agreements with the states on the Gonski school funding reforms, negotiated by the former Labor government.

Pyne has said the new government is planning major changes and a possible return to a Howard-era system after 2014. Having each invested many months negotiating the finer points of a Gonski deal, this dramatic change in policy has understandably raised the ire of a number of the states.

In the public media battle that has ensued, some curious legal claims have been made by both sides. Pyne has suggested that the Commonwealth is not bound by agreements negotiated with Victoria and Tasmania because those states had failed to “sign” a final agreement with the Commonwealth. This is despite the fact that Tasmanian premier Lara Giddings insists that a final deal was reached verbally with then-prime minister Kevin Rudd prior to the election.

In contrast, NSW education minister Adrian Piccoli maintains that his state has signed a “binding agreement” and therefore that it must be honoured by the Commonwealth. NSW premier Barry O'Farrell has reportedly written to prime minister Tony Abbott seeking assurances that NSW will maintain its funding quota on this basis.

So, to support their positions, it appears that everyone is resorting to claims about the legal status of the agreements reached prior to the election. But what exactly is an intergovernmental agreement? Is it legally binding like a contract? Does it matter that Victoria and Tasmania did not sign one while New South Wales did?

In Australia’s federal system, intergovernmental co-operation is critical to achieving policy objectives. This is primarily because the powers of each level of government are limited by the Constitution. Therefore, combining the authority of both by consensus can overcome constitutional constraints and assist in achieving regulatory consistency across jurisdictions.

The need for intergovernmental cooperation is also exacerbated by what is known as a “vertical fiscal imbalance”. This means that while the Commonwealth possesses most of the capacity to raise tax revenue, the states hold most of the legislative powers to spend in critical policy areas. To achieve policy objectives, therefore, there must be significant transfer of revenue from the Commonwealth to the states. This often involves extensive negotiation and intergovernmental agreements.

In recent times, intergovernmental agreements have formed the basis for a number of high-profile collaborative breakthroughs. For example, in 1995, intergovernmental agreements provided the backbone for a national regulatory framework for trade practices and competition policy.

In 1999, intergovernmental agreements were successfully negotiated in relation to the distribution of GST revenue to the states. Most recently, in 2013, the Commonwealth reached agreement with the “Basin states” over the ongoing use and protection of the Murray-Darling River Basin.

Common law contracts and intergovernmental agreements do have some features in common. For example, they can take verbal or written form, or be made up of a combination of both. Also, in the instances when they are formally drafted, it is not uncommon for the parties to “sign” them to show that they represent the final terms agreed in negotiations.

On the other hand, there are key aspects of intergovernmental agreements that make them very different from contracts. The most critical of these is that while a contract derives its binding nature from an intention to form legal relations, intergovernmental agreements are almost always political undertakings only. For this reason, the High Court has recognised that in most cases, intergovernmental agreements do not contain legally enforceable obligations.

Accordingly, in legal terms, it is likely to make little difference whether NSW “signed” an agreement with the Commonwealth while Victoria and Tasmania did not.

Nonetheless, there is an important qualification. Although intergovernmental agreements do not generally operate like legally binding contracts, it is arguable that they should be accorded similar respect by the parties to the arrangement. This is because they play a critical role within the contemporary federal system, often leading to them being described as embodying “soft law”.

In the absence of due respect for the finality of arrangements, the willingness of political actors to place reliance on these agreements may collapse entirely. No agreement could be guaranteed to hold any value beyond the next federal or state election. That could have serious and debilitating ramifications for medium and long-term planning and implementation in some of the most critical policy fields.

Governments then, should not be so quick to dismiss these agreements. It may be more prudent to pay heed to the wider institutional impact of embarking on significant changes to collaborative arrangements before actually doing so.

Shipra Chordia is Director of the Federalism Project within the Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, UNSW.

This opinion piece was first published in The Conversation.