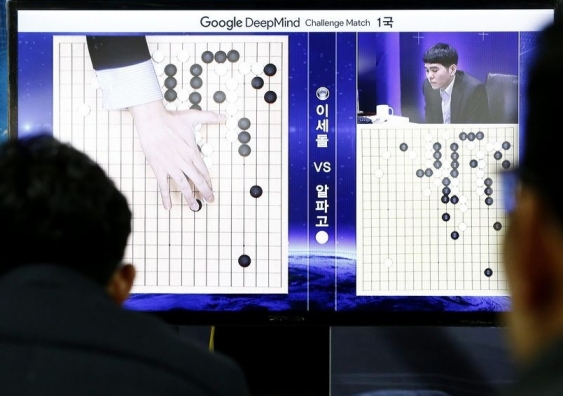

AI has beaten us at Go. So what next for humanity?

South Korean Go champion Lee Se-dol finally beat the AlphaGo Software after three straight losses last week, but AlphaGo's success remains a landmark moment, writes Toby Walsh.

South Korean Go champion Lee Se-dol finally beat the AlphaGo Software after three straight losses last week, but AlphaGo's success remains a landmark moment, writes Toby Walsh.

OPINION: Back in 1979, the newly crowned world champion of backgammon, Luigi Villa, lost to the BKG 9.8 program seven games to one in a challenge match in Monte Carlo.

In 1994, the Chinook program was declared “Man-Machine World Champion” at checkers in a match against the legendary world champion Marion Tinsley after six drawn games. Sadly, Tinsley had to withdraw due to pancreatic cancer and died the following year.

Any doubt about the superiority of machines over humans at checkers was settled in 2007, when the developers of Chinook used a network of computers to explore the 500 billion billion possible positions and prove mathematically that a machine could play perfectly and never lose.

In 1997, chess fell when IBM’s Deep Blue beat the reigning world chess champion, Gary Kasparov.

Kasparov is generally reckoned to be one of the greatest chess players of all time. It was his sad fate that he was world champion when computing power and AI algorithms reached the point where humans were no longer able to beat machines.

Go represents a significant challenge beyond chess. It’s a simple game with enormous complexity. Two players take turns to play black or white stones on a 19 by 19 board, trying to surround each other.

In chess, there are about 20 possible moves to consider at each turn. In Go, there are around 200. Looking just 15 black and white stones ahead involves more possible outcomes than there are atoms in the universe.

Another aspect of Go makes it a great challenge. In chess, it’s not too hard to work out who is winning. Just counting the value of the different pieces is a good first approximation.

In Go, there are just black and white stones. It takes Go masters a lifetime of training to learn when one player is ahead.

And any good Go program needs to work out who is ahead when deciding which of those 200 different moves to make.

Google’s AlphaGo uses an elegant marriage of computer brute force and human-style perception to tackle these two problems.

To deal with the immense size of the game tree – which represents the various possible moves by each player – AlphaGo uses an AI heuristic called Monte Carlo tree search, where the computer uses its grunt to explore a random sample of the possible moves.

On the other hand, to deal with the difficulty of recognising who is ahead, AlphaGo uses a fashionable machine learning technique called “deep learning“.

The computer is shown a huge database of past games. It then plays itself millions and millions of times in order to match, and ultimately exceed, a Go master’s ability to decide who is ahead.

Less discussed are the returns gained from Google’s engineering expertise and vast server farms. Like a lot of recent advances in AI, a significant return has come from throwing many more resources at the problem.

Before AlphaGo, computer Go programs were mostly the efforts of a single person run on just one computer. But AlphaGo represents a significant engineering effort from dozens and dozens of Google’s engineers and top AI scientists, as well as the benefits of access to Google’s server farms.

Beating humans at this very challenging board game is certainly a landmark moment. I am not sure that I agree with Demis Hassabis, the leader of the AlphaGo project, that Go is “the pinnacle of games, and the richest in terms of intellectual depth“.

It is certainly the Mount Everest as it has the largest game tree. However, a game like poker is the K2, as it introduces a number of additional factors like uncertainty of where the cards lie and the psychology of your opponents. This makes it arguably a greater intellectual challenge.

And despite the claims that the methods used to solve Go are general purpose, it would take a significant human effort to get AlphaGo to play a game like chess well.

Nevertheless, the ideas and AI techniques that went into AlphaGo are likely to find their way into new applications soon. And it won’t be just in games. We’ll seen them in areas like Google’s page ranking, adwords, speech recognition and even driverless cars.

You don’t have to worry that computers will be lording it over us any time soon. AlphaGo has no autonomy. It has no desires other than to play Go.

It won’t wake up tomorrow and realise it’s bored of Go and decide to win some money at poker. Or that it wants to take over the world.

But it does represent another specialised task where machine is now better than human.

This is where the real challenge is coming. What do we do when some of our specialised skills – playing Go, writing newspaper articles, or driving cars – are automated?

Toby Walsh is a Professor of AI at UNSW and Research Group Leader at Data61.

This opinion piece was first published in The Conversation.