Big challenges, micro solutions: Closing the loop in Australia’s waste crisis

Waste microfactories can transform the manufacturing landscape in Australia, especially in remote locations where waste transportation and processing are expensive.

Waste microfactories can transform the manufacturing landscape in Australia, especially in remote locations where waste transportation and processing are expensive.

Governments and industry around Australia are desperately grappling with the growing waste and recycling problem that has resulted from China’s ban this year on imports of foreign waste.

The ban has resulted in large increases in stockpiles around the nation; meanwhile prices for waste such as glass are at a low point (it is now cheaper to import than recycle glass) and government emergency funding packages and reviews are underway to work out solutions.

This crisis has brought into sharp focus that Australia’s waste is Australia’s problem, at the very same time that consumers, more than ever, are seeking to reduce environmental impacts and create more sustainable outcomes across all areas of our society.

In June, the Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Inquiry into Waste and Recycling, released its report. It is a sobering read.

There are a number of commendable recommendations within the report, including its ‘headline’ recommendations to ban single use plastics by 2023 and a call for a national container deposit scheme. But it could have gone further, given that a solution is available right now to reduce waste stockpiles, encourage innovation, boost Australian manufacturing and create jobs.

China’s ban on imports of foreign waste has resulted in large increases in stockpiles around Australia in 2018. Image from Shutterstock

As detailed on page 88 of the report, technology developed by my team at UNSW’s Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) Centre enables waste streams like plastics and glass to be reformed into valuable resources for use in manufacturing. This can be done at remote and regional locations, where the report calls for special attention on growing waste stockpiles.

Earlier this year Josh Frydenberg, when Federal Environment Minister, called for the incineration of waste to generate energy to be considered by the States, but this should not be part of the solution when new, more effective and sustainable methods of dealing with waste such as ours are now available, and the report rightly does not recommend incineration.

The ACT Government’s current review into waste management strategies aims to help it divert most waste away from landfill and have the local waste and recycling sector be carbon neutral by 2025. Disappointingly, it proposes burning waste for energy as one of its four strategies.

I applaud the ACT Government for its very proactive stance on environmental sustainability and waste management – and its target to increase its already laudable rate of recycling from 70 per cent to 90 per cent – but the process of burning waste to create energy means that recyclable materials are lost forever as forms of renewable resources.

In addition, the NSW Independent Planning Commission in July formally rejected a proposal to build in Eastern Creek in Sydney’s west what would have been the State’s first waste to energy incinerator. This is a great outcome because we know metals can be repurposed over and over as a renewable resource, and even many plastics can be reformed and reused a number of times.

In July, the Victorian Government announced a new multimillion-dollar recycling package to deal with the problem of growing stockpiles of waste and recycling materials due to the China waste ban.

This follows a NSW Government announcement in March of a support package of up to $47 million to help local government and industry to respond to these global changes. The support package is being funded by the Waste Less, Recycle More initiative and provides a range of short, medium and long-term initiatives to ensure kerbside recycling continues and to promote industry innovation.

Again, I commend these Governments for their comprehensive packages but what they both miss is that a solution is available right now to help not only reduce growing stockpiles, but to create local jobs through Australian innovation.

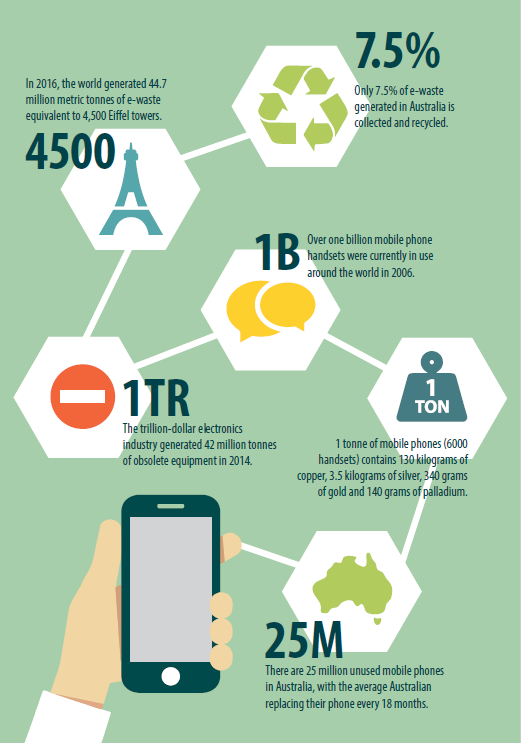

In a UNSW paper recently published in the international publication Journal of Cleaner Production, I reveal our latest SMaRT Centre research about a cost-effective new process for transforming mixed waste glass into high-value building materials without the need for remelting. This new recycling process has the potential to deliver economic and environmental benefits wherever waste glass is stockpiled and is modelled on our recently launched world-first e-waste microfactory.

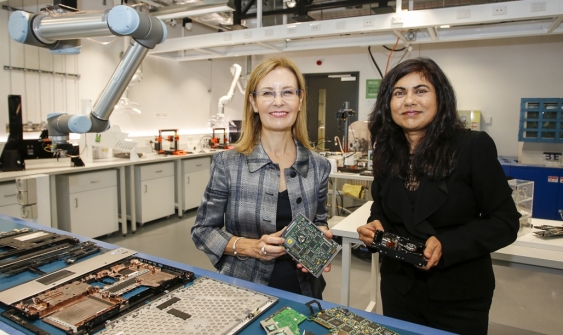

NSW Environment Minister Gabrielle Upton and Professor Veena Sahajwalla at the microfactory launch.

The main problem is that materials currently ‘recycled’ are very low value and thus are treated that way, often ending up in landfill, whereas when treated appropriately these discarded consumer items can be transformed into high value materials to be used over and over again.

Our world-first e-waste microfactory was launched in April by NSW Environment Minister Gabrielle Upton, and is designed to transform the components of discarded electronic items like mobile phones, laptops and printers into new and reusable materials that become inputs and feedstock for the manufacture of new products.

We are now building our first ‘green’ microfactory to take many of the recycled containers and materials put out in council bins, and other waste streams, and convert them into valuable materials such plastic filament for 3D printing, and glass panels for building products.

So, what is a microfactory? Traditional manufacturing often takes place in large and immobile factory sites near raw material supplies or in remote locations. But microfactories can operate on a site as small as 50 square metres and can be located wherever waste may be stockpiled. Costings show an investment in a microfactory can pay off in less than three years.

Our microfactories consist of a series of small machines and devices that use patented technology. The discarded e-waste devices, for instance, are first placed into a module to break them down. The next module involves a special robot to extract useful parts, another module uses a small furnace to separate the metallic parts into valuable materials, while another reforms the plastic into a high-grade filament suitable for 3D printing.

Our microfactories can not only produce high performance materials and products, they eliminate the necessity of expensive machinery, save on the extraction from the environment of yet more natural materials, and reduce the need of burning waste or dumping it in landfill.

Glass stockpiles alone amount to more than one million tonnes per year nationally. Australia produces nearly 65 million tonnes of industrial and domestic solid waste each year. Our new process can transform large quantities of mixed waste glass into glass-based tiles similar in look and performance to various natural and engineered stone products on the market.

So, a solution is at hand, in terms of having the technology to deal with this national problem and being able to operate directly at the sites where the stockpiles are growing. Importantly, this solution can also create a revenue stream from the reformed materials.

UNSW Professor Veena Sahajwalla.

The social and economic benefits from this technology come on top of the environmental benefits. Waste microfactories can transform the manufacturing landscape in Australia, especially in remote locations where typically the logistics of having waste transported or processed are prohibitively expensive. This is especially beneficial for island markets and remote and regional towns.

Through the microfactory technology, we can enhance our economy, stimulate manufacturing innovation in Australia and be part of the global supply chain of valuable materials. This UNSW work is aligned with the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre (AMGC) , which is a key plank of the Australian Government’s Industry Growth Centres Initiative and is part of a $248 million initiative to establish Growth Centres in Australia.

In July, at a special AMGC-sponsored summit at UNSW exploring the reinvention of Australian manufacturing, industry leaders from CSIRO, NSW Environmental Protection Authority (EPA), Innovative Manufacturing CRC, UNSW Science, Engineering and others met to discuss industry challenges and for a tour of the SMaRT e-waste microfactory.

“One-in-10 Australians are employed in manufacturing and this number will continue to grow,” said Michael Sharpe, NSW Director of AMGC. “Collaboration is now essential for manufacturing. We are breaking down barriers by getting industry and researchers working together and producing new materials and processes. We are evolving from an industry stuck in our own factories to breaking down barriers and working together.”

At the Summit, Alan Wigg, Project Officer at NSW EPA, addressed the implications of China's 'National Sword' policy and that country’s recent restrictions on imports of recycled materials and manufacturing.

“There is difficulty finding end markets for recyclable material, and limited local reprocessing. The fundamental problem that needs to be addressed is the state’s dependence on exporting recyclable materials,” said Mr Wigg. “A global shift towards circular economy is occurring, and National Sword presents a unique opportunity for NSW to develop local end markets for recycled products and stimulate industry investment.”

Mr Wigg said a new NSW Government grant, the Product Improvement Program, would target the local manufacturing sector as well as waste recycling facilities. The program will allocate $4.5 million for projects that reduce the amount of unrecyclable material left at the end of the recycling process, with grants supporting up to 50% of the capital costs for equipment or infrastructure.

“One of the main changes to previous programs is including the manufacturing sector,” said Mr Wigg. “A major program objective is to increase the use of recovered plastics, glass, and mixed paper/cardboard in the manufacture of products within NSW. We are encouraging collaboration between suppliers of recycled material and potential users of that material.”

The SMaRT and AMGC partnership has helped attract industry interest in the microfactory technology, and SMaRT is now in partnership with several businesses and organisations including e-waste recycler TES, mining manufacturer Moly-Cop, and Dresden, which makes spectacles.

But unless all levels of government involved in waste and recycling put incentives in place, business and councils will be slow to capitalise on the potential to lead the world in reforming waste into something valuable and reusable.

Televisions and computers piled up for recycling. Image from Shutterstock

The Commonwealth Department of the Environment and Energy recently started the first review of the Product Stewardship Act 2011, along with changes to the National Television and Computer Recycling Scheme. These reviews looking at the effects of the disposal of products and their associated waste are another opportunity for greater sustainable practices and reducing the amount of waste going into landfill and stockpiling.

New materials, critical parts and components can then be exported to the rest of the world, contributing to an ecosystem that supports the economy and is part of the global supply chain. Growing and creating new products enables business of all sizes to develop innovative solutions, build on the back of existing practices, and turn Australian innovation into a solution for one of our most pressing global problems.

UNSW’s Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) Centre is collaborating with various businesses and organisations to help translate our recycling and reformation technology into commercial reality. In one example, we are partnering with disruptive glasses manufacturer and retailer Dresden to design, build and test the manufacture of spectacles from waste plastic such as nylon from fishing nets, milk bottle lids, Lego pieces and other commonly discarded items.

Dresden, its commercial partners, and UNSW recently successfully applied for a $2.7 million grant from the Federal Department of Business’s Cooperate Research Centre program to build a fully automated manufacturing centre where recycled waste plastics are transformed into high quality, stylish, low-cost spectacle frames of exceptional durability.

The novel plastic recycling technology has the potential to be applied more widely to produce other high performance products whilst reducing waste and environmental degradation. While Dresden currently uses some reformed waste plastic in its frames, the challenge for UNSW’s SMaRT as part of this program, is to develop a reliable way to use 100 per cent waste plastic in the manufacturing process that is simplified and closed loop with zero waste. The project partners recently jointly commenced the project and aim to conclude it by achieving the aim to have developed a full commercial production facility.

In other examples, SMaRT is separately collaborating with Planet Ark and Nespresso on two projects related to the waste from coffee drinking. With Planet Ark, we are collaborating to find and develop new end uses of coffee waste and to trial them in potential manufacturing processes.

And with Nespresso, we are looking at ways to capture and collect coffee capsules to reform the metals into valuable materials for reuse. We are looking at a new process that does not involve a traditional smelting process that is expensive, complex, and unable to meet the dynamic needs of smaller scale processes to reform waste into high value materials from many locations as can be done by our microfactories in an affordable way.

Australian Research Council (ARC) Laureate Professor Veena Sahajwalla is an internationally recognised materials scientist, engineer and innovator at UNSW Sydney who is revolutionising recycling science. She is renowned for pioneering the high temperature transformation of waste in the production of a new generation of ‘green materials’.

This article is republished from The Australian Quarterly.