OPINION: All modern Olympics employ directors who stage-manage the huge spectacle of the Games – and Sochi 2014 is no different. So what does this stage management tell us, internationally, and what is it intended to communicate to a Russian domestic audience?

The popular Russian commentator Victor Shenderovich astutely observed that the Sochi Olympics and other events in “the incessant hysterical line of patriotic festivals accompanying Putin’s illegitimate rule” resembled the 1936 Berlin Olympics – famously documented by Leni Riefenstahl in her film Olympia – because they were intended to legitimise what he sees as the regime’s crimes.

Shenderovich was instantly labelled a “fascist” – but the ideas underlying his observation deserve some consideration.

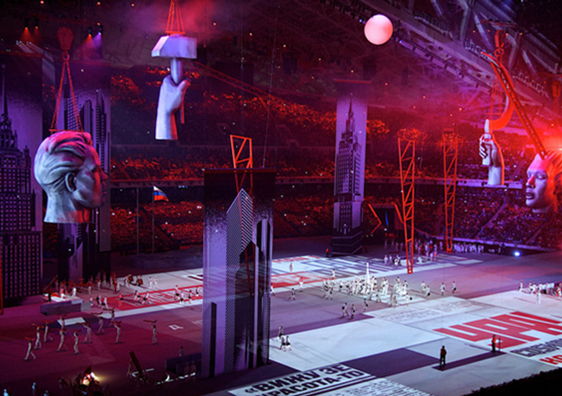

The Sochi Opening Ceremony – was masterminded by Konstantin Ernst, Russia’s most powerful producer and head of Channel One, Russia’s largest state-controlled television network.

The opening was at once predictably spectacular in presenting Russia’s aspirational symbolic understanding of its own history – but also surprisingly (perhaps for Putin) a little camp, with noughties girl band TaTu – Russia’s world-famous “fake lesbians” – among the performers.

Simultaneously and without contradiction it presented a celebration of Russia’s classical and at times surreal cultural heritage.

The New Yorker has described Ernst is the chief visual stylist of the Putin era. A professional pragmatist, he has established the myth of the era, its visual style, attitude and most importantly its nuanced emotional life that blends sentimentality and nostalgia with a sense of mystical power.

Olympian spectacles

The current Winter Olympics are a far cry from the 1980 Moscow Summer Games in terms of spectacle and readying the audience in advance.

In 1980 the focus was on TV informational programming, documentaries, kids animation and, of course, the famous card stunt that was used for the first time at an opening ceremony.

Paradoxically, it was also the first time a mascot was used at a sporting event that then went on to gain a life of its own and enormous commercial success. Mishka, the Russian bear mascot, appeared at the opening and closing ceremonies, in the guise of numerous merchandising products (I still have mine) and as a character in the Olympics episode of the much loved Russian animation, Nu Pogodi! (Just you Wait!).

The opening ceremony integrated a childlike vision of Olympic history with Soviet cosmonauts, Greek chariots and Russian troikas, high formality with an elaborate dance suite celebrating the Friendship of all Peoples (or at least the 15 Soviet Republics) but performed to the Russian folk song Kalinka and then Widespread is my Motherland, made famous in Alexandrov’s mass spectacle Stalin-era blockbuster musical, Circus (1936).

The vision from Moscow in 1980 was all about soft, cuddly power, not a spectacle of a mature, sentimental and at times surreal empire that we are seeing in Sochi.

The Sochi opening ceremony was a summary of the Putin era: new media and classicism stuck together with pathos to celebrate a robust sense of nationalism, pride and a symbolic resurrection of Empire. Let’s not forget that Ernst developed Russia’s first major blockbuster, Night Watch (2004), a brilliant action thriller about vampires and mystical forces that were fighting for the soul and salvation of Russia.

Russian athleticism on screen

In contrast to Moscow 1980, there has been a spate of films preparing Russian audiences for the appropriate emotional response to the Sochi Olympics. It’s not about the medals and the victories – but the passionate relationship of the athlete to their community and country.

There Are Only Girls in Sport, released on February 6, is just one of those films, about the Russian women’s snowboard team. Three long-haired 18-year-olds get away from a chase by riding snowboards down a professional track.

Their skills are noticed by the women’s Olympic coach who invites the girls to join her team. Problem is that they are not girls and a whole range of unexpected adventures ensues especially with the American women’s snowboarders.

Last year’s top-grossing film, Legend No. 17 primed audiences to focus not only on the sporting heroes and medals, but on the human element of their rise to the top and their emotional and family life in the context of international sporting success.

Legend No. 17 was a powerful, heartbreaking tale of the rise of Russia’s greatest ice-hockey player – Valeri Kharlamov – to lead an unfancied Russian amateur team against the might of Canada’s professionals and win against the odds. Much more than a sport film, this was a potent biopic that showed the power tussles in the sporting bureaucracy and how that played out on real people with a few historical revisions thrown in to ensure maximum emotional response.

Riefenstahl’s elegant but disturbing Olympia (1938) has nothing on the Sochi Olympics. They are the culmination of the complex cinema, television and mythology of the ongoing Putin era, an era that is remarkable in its blending of melodrama, sentimentality and sense of a mystical Empire.

The view from the outside

The Western media’s coverage of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics has been – on the whole – negative, with journalists taking every opportunity to grumble about their living conditions and ridicule the Russians over minor preparation details.

And the criticisms levelled at Russia over its treatment of gay and lesbian people have – of course – been aired internationally.

But Russian media’s representation of the Games has been remarkably consistent – drawing on the tried and tested bread and circuses formulae but with a nice mix of traditional Russian sentimentality, professionalism – and a demonstration of the Empire’s capacity to eliminate any opposition or at least to stifle it with money.

Dr Greg Dolgopolov is a Lecturer in Film in the School of the Arts and Media, UNSW.

This opinion piece was first published in The Conversation