Tumour-trained T cells go on patrol

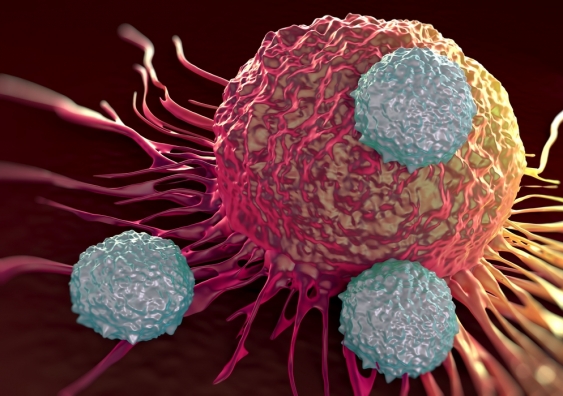

In cancer, immune cells infiltrate tumours – but it hasn’t been known which immune cells exit the tumour or where they go next.

In cancer, immune cells infiltrate tumours – but it hasn’t been known which immune cells exit the tumour or where they go next.

Dr Meredith Ross

Garvan Institute of Medical Research

0439 873 258

m.ross@garvan.org.au

"Tumour-trained" immune cells – which have the potential to kill cancer cells – have been seen moving from one tumour to another for the first time.

The new findings, which were uncovered by scientists at Sydney’s Garvan Institute of Medical Research, shed light on how immune therapies for cancer might work, and suggest new approaches to developing anti-cancer immune therapies.

The study, which was carried out in mice, is published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA (PNAS).

Metastatic cancer, in which cancer has spread to other sites beyond the primary tumour, is responsible for almost all cancer deaths, and treatment options remain very limited. New immune therapies that help the body’s own immune T cells to attack cancer cells within tumours are showing promise in metastatic cancer – yet little is understood about how these therapies function.

“We know that T cells and other immune cells accumulate inside tumours – but until now we’ve known very little about what happens next. How does the environment within the tumour change the cells? Do they leave the tumour? Which types of immune cells leave? Where do they go, and why?” says Dr Tatyana Chtanova, head of the Innate and Tumour Immunology lab in Garvan’s Immunology Division and UNSW Conjoint Senior Lecturer, who led the research.

To watch tumour-trained immune cells travelling through the body, Dr Chtanova and her team used an innovative photoconversion strategy – in which all the cells in a mouse are labelled with a green fluorescent compound, and only those within a tumour (including immune cells) are turned to red by shining a bright light on the tumour.

“Before, we could only guess at which immune cells were leaving tumours,” says Dr Chtanova.

“So to see these red cells moving in a sea of green, as they exited a tumour and travelled through the body, was remarkable.

“We saw immune cells leaving the tumour and moving into lymph nodes – and, importantly, we could see immune cells moving out of one tumour and into another, distant tumour.”

The researchers were surprised to see that the mix of immune cells leaving tumours was sharply different to the mix of immune cells going in.

“We found, unexpectedly, that T cells were the main immune cells to exit tumours and move to lymph nodes and other tumours – even though they represent only a fraction of the immune cells that enter tumours,” Dr Chtanova notes. “And some classes of T cell, such as CD8+ effector T cells which promote tumour destruction, were more likely to exit the tumour.

“This tells us that there’s strong control over the tumour-exiting process.”

Importantly, the T cells that had been exposed to the tumour’s microenvironment and then exited the tumour were more activated, and had a stronger cytotoxic (cell-killing) activity, than those that did not enter the tumour.

“What we suspect is happening is that, within the tumour, these T cells are acquiring knowledge about the cancer that helps them to seek and destroy tumour cells," Dr Chtanova said.

“It’s possible that these T cells "on patrol" – which leave one tumour and move to another – are using their new-found knowledge to attack cancerous cells in the second tumour.”

The research team are now working on ways to prompt activated T cells to exit tumours in greater numbers, Dr Chtanova adds.

“Ultimately, we’re working to understand more deeply the relationships between immune and cancer cells, so that we can design approaches to empower the immune system to destroy cancer."