Riversleigh fossil reveals a fearsome ancient killer

An ancient fox-sized cousin of the Tasmanian tiger was a fearsome killer that hunted large prey, a study of a well preserved skull from Queensland's Riversleigh World Heritage Site suggests.

An ancient fox-sized cousin of the Tasmanian tiger was a fearsome killer that hunted large prey, a study of a well preserved skull from Queensland's Riversleigh World Heritage Site suggests.

An ancient fox-sized cousin of the Tasmanian tiger was a fearsome killer that hunted large prey, a study of an extremely well preserved skull from the Riversleigh World Heritage Fossil Site in northwestern Queensland suggests.

The 16 to 11.5 million year old fossil skull of the meat-eating marsupial, Nimbacinus dicksoni, was unearthed and analysed by researchers at UNSW and the University of New England.

Nimbacinus dicksoni is a member of an extinct family of Australian and New Guinean marsupial carnivores, called Thylacinidae. Apart from for one recently extinct species – the Tasmanian tiger - the majority of information known about species in this family stems from recovered skull fragments.

The team, led by Dr Marie Attard of the University of New England, applied virtual 3D reconstruction techniques and computer modelling to reconstruct the skull of Nimbacinus, digitally 'crash-testing' and comparing it to models of large living marsupial carnivores, including the Tasmanian devil, spotted-tailed quoll and northern quoll, as well as to the Tasmanian tiger.

They found that the similarity in mechanical performance of the skull between N. dicksoni and the largest quoll, the spotted-tailed quoll, was greater than the similarity to the Tasmanian tiger.

This suggests that N. dicksoni, a medium-sized marsupial weighing about 5 kg, had a high bite force for its size, was predominantly carnivorous, and was likely capable of hunting vertebrate prey that exceeded its own body mass.

"Our findings suggest that Nimbacinus dicksoni was an opportunistic hunter, with potential prey including birds, frogs, lizards and snakes, as well as a wide range of marsupials,” says Dr Attard, who studied the fossil as part of her PhD research at UNSW

“In contrast, the iconic Tasmanian tiger was considerably more specialized than large living dasyurids and Nimbacinus, and was likely more restricted in the range of prey it could hunt, making it more vulnerable to extinction,” she says.

The study is published in the journal PLOS ONE.

UNSW scientists have led research at the Riversleigh World Heritage Fossil Site for 37 years.

“What makes this study of mechanical capacity possible is also what makes Riversleigh globally so stunning – a deliciously high biodiversity of weird and wonderful creatures, and simply extraordinary preservation,” says study author, Professor Mike Archer, of the UNSW School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences.

The 15 million year old cave deposit, AL90 Site, where the Nimbacinus was found, has produced many hundreds of well-preserved fossils.

“It was a very exciting deposit to work, with skulls and skeletons popping up all over the place as we excavated each ancient floor, one on top of another, that had filled up the cave. And of course it’s just one of more than 200 fossil-rich sites spanning the last 26 million years at Riversleigh, with more new sites being found every year,” says Professor Archer.

“The Nimbacinus skeleton was one of the first and most amazing things we encountered in the AL90 deposit. Apart from the modern species, it is the only other extinct thylacinid skeleton known and has provided many insights into the evolutionary origins and behaviours of Australia’s carnivorous marsupials.

“We found, from the posture of the skeleton, that it had given up trying to get out of the cave into which it had fallen so long ago. It had folded its arms, and put its head down for a quiet little 15 million-year-long nap. Hence, we nick-named it the ‘Philosophical Thylacine’,” Professor Archer says.

Media contacts:

Dr Marie Attard: marie.attard@une.edu.au

Professor Mike Archer: 9385 3446, m.archer@unsw.edu.au

UNSW Science media: Deborah Smith 9385 7307, 0478 492 060, Deborah.Smith@unsw.edu.au

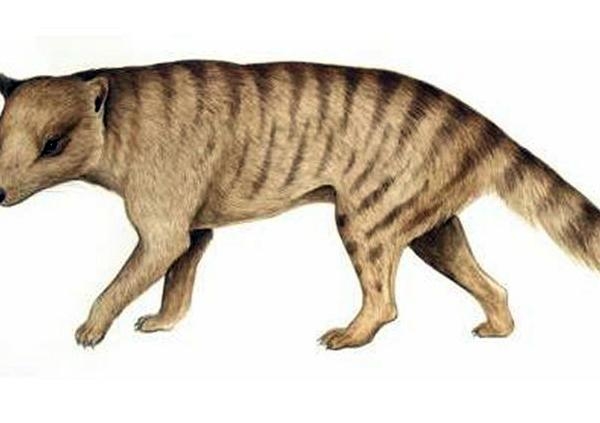

An illustration of Nimbacinus dicksoni Credit: Anne Musser