Wealthy landlords and more sharehousing: how renting is changing

Landlords and tenants alike are adapting their behaviour in response to changes in affordability and new technologies.

Landlords and tenants alike are adapting their behaviour in response to changes in affordability and new technologies.

OPINION More people are becoming heavily indebted by buying rental properties and shared accommodation is flourishing, as third party tech platforms help people find a place without a real estate agent.

A new report from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute explains how the private rental market is changing over time for both landlords and tenants.

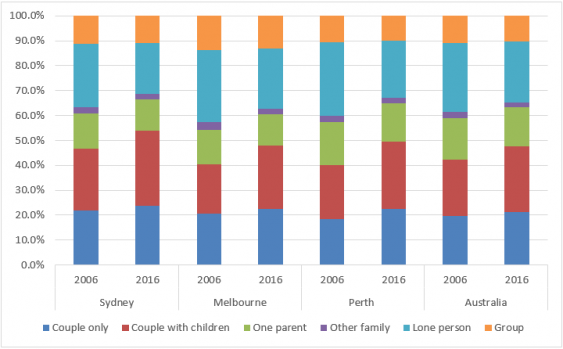

Over the 10 years to 2016, the number of renters grew 38% - twice the rate of household growth. More renters now are couples, or couples with children, so it seems the sector is shaking its image of unstable housing or perhaps these people are left with few other options.

Households by type, 2006 and 2016

Source: Calculated from the ABS Census of Population and Housing, various years

The report analyses data from the 2016 Census, the 2013-14 Survey of Income and Housing and the 2014 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. It also draws on interviews conducted with 42 people involved in all aspects of the private rental sector: financing, provision, access and management.

Rental property ownership also grew. We found the number of households with an interest in a rental property grew and the number that own multiple properties grew slightly as well.

But the typical landlord is still the conventional “mum and dad” investor. Two-thirds of rental investor households have two incomes, and 39% have children.

However they are also mostly high-income and high-wealth households: 60% are in both the highest income and highest wealth bracket. Interestingly, about one in eight landlords is themselves a private renter.

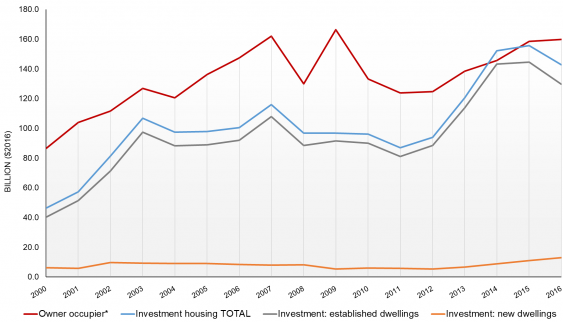

Housing finance, 2000 - 2016

Source: Calculated from ABS cat. no. 5609 Table 11. Notes: *owner occupier excludes amounts for refinancing of established dwellings; amounts have been inflated to 2016 dollars by the All Groups CPI (Australia).

The biggest change in ownership is in finances: owners of rental properties are relying more heavily on debt.

The people we interviewed highlighted the Australian Prudential Regulation Authorities’ (APRA) guidance to lenders on loan serviceability calculations as having the greatest impact on overall investment levels and investor decisions.

Adding to the complexity is the proliferation of intermediaries, such as mortgage brokers and wealth advisers. These advisers are telling borrowers what lenders and loan products to use to maximise their borrowing power and negotiate lender and regulator requirements.

Houses are the most commonly rented in Australia, but everywhere rental markets are moving away from this and towards dwellings like apartments.

There’s now more diversity in rental properties too, for example, the building of high-rise student accommodation, “new generation boarding houses” and granny flats.

These allow landlords to house more people in the one building, increasing revenue and making management more efficient.

The informal sector of shared accommodation appears to be flourishing, like improvising shared rooms and lodging-style accommodation in apartments and houses.

People have moved from finding rentals in real estate agents’ high street offices and onto online platforms. New third-parties like apps and other digital platforms offer non-cash alternative bond products, schedule property inspections, collect rents, and organise repairs.

Even though these technological innovations avoid agents, agents have in fact increased their share of private rental sector management. Agents themselves are use these platforms to change their businesses, and the structure of their industry.

Our research found that revenue from an agency’s property management business (its “rent roll”) has become increasingly important. Some players in the industry are consolidating their businesses around it, to make higher profits from tech-enabled efficiencies.

Houses are the most commonly rented in Australia, but everywhere rental markets are moving away from this and towards dwellings like apartments. There’s now more diversity in rental properties too, for example, the building of high-rise student accommodation, “new generation boarding houses” and granny flats.

However, the real estate business still depends on building personal relationships, particularly in high-end markets.

The new tech platforms of the private rental sector raise issues for tenants too, particularly in terms of the personal information they collect. For example, one of the online platform operators told us they looked forward to using applicants’ information to score or rank applicants. Another one of the new alternative bond providers uses automatic “trust scoring” of personal information to price its product.

These innovations may be convenient to use, and may give some tenants an advantage in accessing housing - but at the expense of others who are already disadvantaged.

If the private rental sector is going to meet the demand for settled housing, governments will have to intervene. This can’t be left to technological innovation, or higher income renters exercising their consumer power.

Federal or state governments could create public registers of landlords, or licensing requirements, to police landlords who are not “fit and proper” and exclude them from the sector.

There could also be stronger laws around tenancy conditions and protections for tenants against retaliatory action. The Poverty Inquiry in the 1970s set the basic model of our present laws and they haven’t changed much.

Tenants’ personal information also needs to be protected, to properly take account of the rise of the online application platforms; another is the informal sector, which is currently in a regulatory blindspot.

![]() The popular emphasis on “mum and dad” investors diminishes expectations of landlords. Rental property investment should be regarded as a business that requires skill and effort. As for-profit providers of housing services, landlords should be held to standards that ensure the right to a dignified home life.

The popular emphasis on “mum and dad” investors diminishes expectations of landlords. Rental property investment should be regarded as a business that requires skill and effort. As for-profit providers of housing services, landlords should be held to standards that ensure the right to a dignified home life.

Chris Martin is a Research Fellow, City Housing, in the City Futures Research Centre, UNSW.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.