Materials science PhD candidate Lorenzo Travaglini from Italy is the inaugural recipient of a scholarship created for European students by businessman Pietro Bergamaschi to repay the generosity he received himself at UNSW as a young Italian immigrant.

Bergamaschi arrived in Australia in 1967 in search of better opportunities, armed only with a degree in industrial chemistry. “I didn’t even speak a word of English,” he recalls.

The young Italian started out at Transfield, an infrastructure company, in their galvanising department called Zincline, and later was interviewed for a job at the UNSW School of Metallurgy. There Bergamaschi met Professor Greig Wallwork, who recognised the potential of Bergamaschi’s background in industrial chemistry.

Officially, Bergamaschi believed he was being interviewed to be a laboratory assistant. In fact, Wallwork was testing Bergamaschi to see if he had the ability to be a postgraduate research student. This was despite Bergamaschi having non-existent knowledge of the English language that prevented him from taking any exams.

From School of Metallurgy funds, Wallwork created a scholarship especially for Bergamaschi, so he could pursue a higher research degree.

Bergamaschi was in his element, studying the formation of Titanium Oxide, which was achieved by alloying Titanium metal with Titanium Dioxide. By subtracting Titanium metal from the alloy, Titanium dioxide would be left behind at various concentrations of oxygen.

This work was done under the tutelage of Professors Wallwork and Alexander Jenkins - both renowned researchers who had been integral in establishing UNSW's leading reputation in Materials Science during the University's formative years.

Jenkins was also a World War 11 veteran, who had flown Lancaster bombers over Europe as a member of the RAAF 460 squadron. His remarkable experiences as the sole survivor of his squadron after an intense campaign in Belgium near the German Border are recorded in the Australians at War Film Archive.

Bergamaschi graduated in 1970 with a Master's of Science. Ten years later, when he saw Wallwork again at a retirement dinner, he made an offer to repay the scholarship and funded a Master's of Science scholarship.

Last year, Bergamaschi also financed the Pietro Bergamaschi European PhD Scholarship, which helps cover the living expenses of a European student seeking to complete a PhD in the UNSW School of Materials Science and Engineering.

“I have a great debt to Greig, the School of Metallurgy and to the University,” says Bergamaschi.

“They not only offered me a job when I arrived in Australia not knowing English, but I had the chance to do what I liked and learn English at the highest level.”

“My hope for the scholarship is that someone from Europe will pay Australia back by contributing to research and development.”

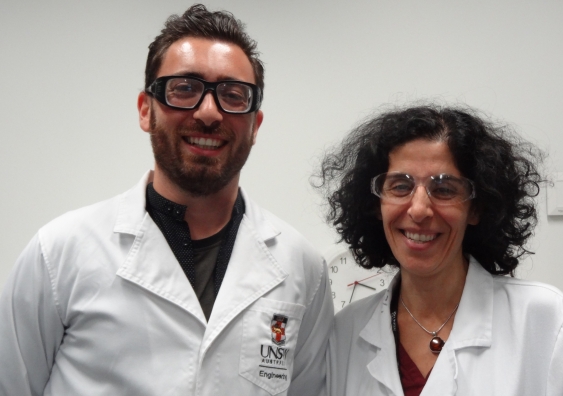

Lorenzo Travaglini, the first recipient of the Pietro Bergamaschi European PhD Scholarship, and his PhD supervisor Dr Damia Mawad.

The inaugural recipient of the scholarship, Lorenzo Travaglini, studied physics at Bergamaschi’s alma mater, the University of Bologna. He was working at a bank to support himself while searching for research positions when he received the good news that he says has changed his life.

“I was so happy, I couldn’t believe it. I knew this was what I wanted to do,” says Travaglini, who is now working with Dr Damia Mawad to develop conductive polymers - a type of flexible material with electrical properties that have potential for repairing damaged tissues.

“If it wasn’t for the scholarship, it’s highly likely I would still be working at the bank,” he says.

When Bergamaschi saw Travaglini’s CV, he knew immediately he was a strong candidate who was willing to face any challenge life would throw at him.

“I saw that Lorenzo was a fighter who knew that life was difficult,” says the successful businessman. “He was a person who had sacrificed part of his life to achieve a result, and I was sure he was able to adapt himself and come up with good results.”

Bergamaschi was there to welcome Travaglini at the airport and witness the moment the young Italian saw the new UNSW Materials Science and Engineering laboratories for the first time.

“The good thing about Lorenzo is that he recognises the value of the School. When he first arrived, his eyes were popping out of his head,” says Bergamaschi.

One of the first things Bergamaschi impressed on Travaglini was to try and continue the cycle of generosity.

“He said: ‘In the future, if you have the possibility to do so, you must do the same’,” says Travaglini.

Bergamaschi was so pleased with the outcome of the first scholarship that he has offered a second one, which has been awarded to an Austrian student who will begin at UNSW in June.

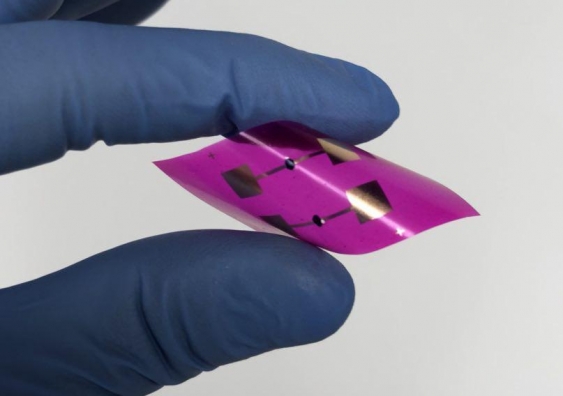

Prototype of the flexible polymer patch being developed by Dr. Damia Mawad’s research group.

Meanwhile, Travaglini’s research goal is to develop a prototype flexible device so thin it resembles cellophane that can be used in heart surgery instead of stitches.

The heart is one of the strongest muscles in the human body, but a single heartbeat is dependent on an intricate cascade of electrical signals. After a heart attack, a piece of heart tissue dies, which means it can no longer conduct electricity.

“The final project is to develop a conductive patch like a transistor that you can actually apply on the heart,” says Travaglini.

The patch will act as a bridge to spread the electrical signal between the healthy and damaged part of the heart. The patch would be attached to the heart muscle with a thin layer of chitosan, a compound commonly found in crab shells, which become sticky when irradiated with a green laser.