I am currently at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing, where controversial CRISPR scientist Jiankui He presented his research just a few hours ago. He also answered questions from gene experts Robin Lovell-Badge (Crick Institute) and Matt Porteus (Stanford), plus assembled audience members and the media.

It’s just two days since reports first aired that Jiankui He had used CRISPR to edit human embryos, and that twin girls, Lulu and Nana, had been born.

The mood of the meeting is tense. Before these reports, there had been confidence among those in the field that the world was moving as one – cautiously inching forward with CRISPR gene editing technology.

But suddenly the forbidden fruit has been plucked, and some even worry that public confidence may falter.

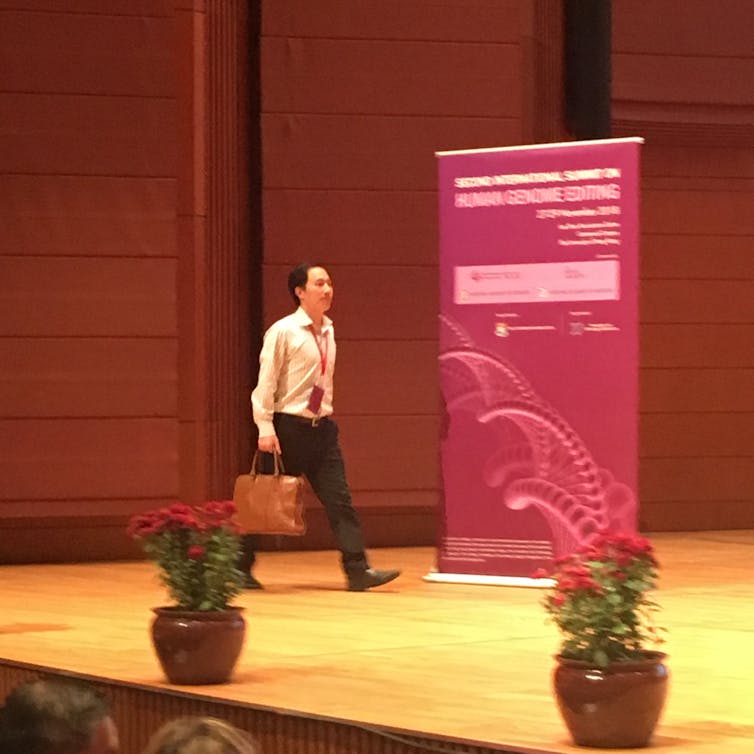

Jiankui He arrives to speak at the 2nd International Summit on Genome Editing, Hong Kong November 28, 2018. Merlin Crossley, Author provided

Jiankui He focused on removing a gene called CCR5, critical for the HIV virus to enter cells. He aimed to mimic a natural mutation which confers resistance to HIV. This work is now on hold and an uncomfortable international discussion has begun.

The stories, and a video published by Jiankui He in which he explains the apparent work, have created widespread condemnation on scientific and ethical grounds.

If the claims are correct, and they are certainly plausible, this is the first time CRISPR has been used to create permanent changes in human genomes – changes that would be passed on to future generations.

Jiankui He himself is experienced in using CRISPR – he first carried out pilot experiments in mice, monkeys, and then non-viable human embryos. He also says he carried out a genomic analysis on the embryos before implantation, and that he had enrolled and worked with a further six couples in this trial before it was paused. One of the additional women may be in the very early stages of pregnancy.

International consensus

China is a major scientific power. The capability of Chinese researchers is highly respected, but if the international consensus on being transparent and cautious about gene editing does not hold the future is difficult to predict.

Jiankui He’s host institution – the Southern University of Science and Technology – published a statement saying he had been on leave at the time of the trial and that it was not conducted at their institution.

Currently other Chinese researchers in attendance at the conference are among the strongest critics of this work. Several have indicated that it breaks the rules governing genetic research in China.

Robin Lovell-Badge (Crick Institute), Jiankui He and Matt Porteus (Stanford) prepare to talk on stage. Merlin Crossley, Author provided

Be that as it may, the results seem clear. Today’s presentation suggests this was a thoroughly planned and executed project, where Jiankui He carefully communicated his results, first by video, and then followed up with his conference talk to share his data. Details on the process, the specific mutations and analysis used to screen for potentially harmful “off-target” genomic changes were also presented today.

On the data shown, it does look like genome editing was achieved. Though the actual mutations did not end up mimicking naturally occurring mutations in CCR5, so we can’t tell – and indeed may never know - whether the twins are resistant to HIV.

He also indicated the work had been submitted for publication in a peer reviewed journal.

Many questions

Hosting panel members Robin Lovell-Badge and Matt Porteus asked questions of Jiankui He after he had finished presenting – the whole presentation and the Q&A is available for viewing here.

The Chair of the Summit, Nobel Laureate David Baltimore, spoke from the floor after the panel session. He expressed concerns that the work did not comply with the commitments made at the first Gene Editing Summit held three years ago, whereby:

it would be irresponsible to proceed with any clinical use of germ line editing unless and until the safety issues had been dealt with.

He added:

I don’t think it has been a transparent process. We only found out about it after it’s happened and after the children are born. I personally don’t think that it’s medically necessary.

And further:

I think there’s been a failure of self-regulation by the scientific community because of a lack of transparency.

He emphasised these comments came entirely from himself.

A statement from the organisers of the summit will be released tomorrow, and I expect it will re-iterate the need for caution, openness in planning and full transparency.

And, despite the shock, that’s what I hope we’ll get – ultimately CRISPR technology is slow, expensive and is used at the level of individuals not populations.

There won’t be a tsunami but there will be plenty to discuss. And we will have time, just as we did when other expensive medical landmarks occurred - heart transplants, test tube babies, and somatic gene therapy. This is bigger, but I believe we can still get back to a consensus and find the right path.

Merlin Crossley, Deputy Vice-Chancellor Academic and Professor of Molecular Biology, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.