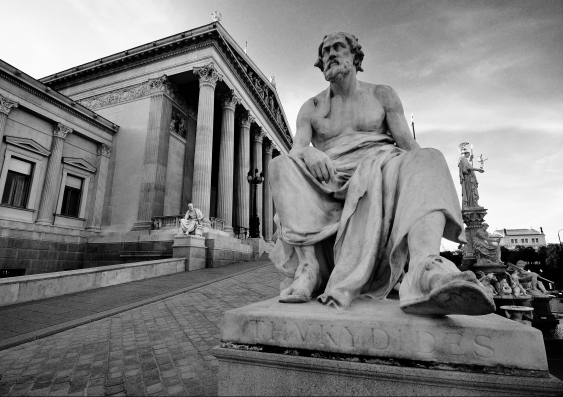

Beijing must beware the Thucydides trap

China would do well to heed the warning by the great Athenian historian Thucydides about the heightened risk of conflict when a rising power challenges the existing international order, writes Alan Dupont.

China would do well to heed the warning by the great Athenian historian Thucydides about the heightened risk of conflict when a rising power challenges the existing international order, writes Alan Dupont.

OPINION: It’s rare for an Australian prime minister to quote from a classical Greek text and even rarer in the context of our relations with the US and China. But in his speech to a US think tank in Washington, Malcolm Turnbull cited the great Athenian historian Thucydides in warning of the heightened risk of conflict when a rising power challenges the existing international order and the position of the previously dominant state — the so called Thucydides Trap.

In a clear reference to US-China relations, and the tensions being generated over China’s ambit claims to island territories and resources in the Western Pacific, Turnbull reminded Asia’s rising power that if it wants to be welcomed by the world then it must also work to reassure its neighbours that its intentions are good.

Unfortunately, China has abjectly failed Turnbull’s litmus test. In forcibly pressing its claims to reefs and islands in the South China Sea, Beijing has not only alienated many of its neighbours but also raised deep concerns about its ultimate intentions. In recent months, China has continued its land reclamation activities in the South China Sea, flown passenger aircraft onto a new runway on contested Fiery Cross Reef, which sits astride the region’s main shipping routes, and attempted to enforce an air and sea exclusion zone around artificial reefs well beyond the 500 metre safety zone to which they are entitled. Beijing has also provocatively moved a deep sea oil rig into waters off the Vietnamese coast, which risks another stoush with Hanoi and a re-run of Vietnam’s 2014 anti-Chinese riots.

There are two opposing positions in Australia about the right response to China’s aggressive strategy. The “don’t rock the boat” view is that we shouldn’t do anything to offend China because of the importance of the economic relationship. The “realist” view is something has to be done to signal our displeasure and uphold our commitment to international rules and norms.

Realists seem to have prevailed in the deliberations of the National Security Committee of Cabinet, which will almost certainly result in Australian Defence Force ships and aircraft more frequently transiting through disputed areas of the South China Sea. The point of these transits would be to demonstrate support for the principle of freedom of navigation on the high seas and assert the illegitimacy of China’s maritime land grab as well as those of other claimants.

Before ramping up freedom of navigation operations the government must consider not just the when, and the how, but the likely domestic and regional response to ensure the costs do not outweigh the benefits. FONOPs should be conducted on a regular, not occasional basis, using our maritime patrol aircraft and frigates. If the point is to deliver a message to China then the operations can’t be so discreet that no one knows about them, as has occurred in the past. But neither should they be accompanied by megaphone diplomacy and orchestrated publicity. The appropriate descriptors are lawful, low-key and routine.

The operations should be conducted unilaterally to achieve clear defence and foreign policy objectives. This means no joint FONOPs with the US and Japan. We don’t need to hide behind another country or gratuitously feed China’s already well developed containment paranoia.

Domestic political support for regular FONOPs is much stronger than “don’t rock the boat” proponents allow. Australians understand the value of strong economic and people-to-people ties with China. But public anxiety about Beijing’s strategic ambitions has grown in consonance with its cavalier approach to the rights of smaller states in the maritime commons.

Provided the case for FONOPs is persuasively articulated and the operations well executed, the government is unlikely to encounter much opposition from the Left. Greens are not impressed with the wanton destruction of the delicate, marine reef ecology of the South China Sea by China’s dredging operations. And shadow minister for defence, Stephen Conroy, has locked Labor into a robustly pro-FONOPs position, criticising Turnbull for not doing enough to support international maritime law.

Regionally, it’s hard to think of a country that does not share Australia’s concerns about China’s coercive strategy. Beijing will undoubtedly protest against our FONOPs and will pressure us to cede to its territorial claims, as it has with the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and even the US. Chinese coastguard and military harassment of our ships and planes is a real possibility. Commercial retaliation is less likely because it would be overwhelmingly counter-productive. China needs our resources as much as we need its investment and trade.

Why take the risk at all? For the simple reason the cost of inaction is greater. China’s game-changing and system-challenging actions have been at the expense of regional stability, the sovereignty of other states, established norms, the maritime commons and the environmental health of the world’s most important sea.

Rather than mollifying China, compliance and inaction by regional states has only encouraged Beijing in its acquisitive territorial and resource policies. If there is no push back, then China will conclude it can take what it wants and do what it likes in the South China Sea.

Given the stakes, increased FONOPs by the ADF would be a measured first response. As a soldier-citizen of the world’s first known democracy, Thucydides well understood that to avoid his trap and ensure a just system, the strong must not be allowed to do as they please.

Alan Dupont is Professor of International Security at UNSW and a nonresident Fellow at the Lowy Institute.

This opinion piece was first published in The Australian.